Some Remarks on Literate Music in the Age of Polyphony

Mar 29 2020Introduction

‘Where there is music, madam, there can be no harm.’

Don Quixote, II.34

If I may be excused for the vanity of talking about something which is particularly dear to me, and with the hope that it may be of value to others, I shall attempt to form a narrative out of the music which most interests me. It ranges from the final cantus firmus masses of Du Fay to the magnificats of Gombert. For such a diverse body of works, it is natural to first search for a convenient label. The hallowed name of “Renaissance music” seems to have outlived its usefulness now that the connotation of a renascence in music which parallels the developments in literature and art is no longer tenable1. Lowinsky’s more subtle term, “Music in the Culture of the Renaissance”, which removes the direct association, nevertheless places the music as a contemporary witness of the rich culture of humanism and classicism in literature and art. It is difficult to explicitly connect the immediate qualities of the best compositions of Palestrina and Lassus, much less those of Gombert, Josquin or Ockeghem, with the virtues of music extolled in the works of classical antiquity. Indeed, it has been aptly stated that the “Renaissance” in music did not begin until 1600 with Monteverdi and the rise of monody, a period that was once universally acknowledge to mark, for music, the boundary between the Renaissance and the Baroque2. The influence of humanism on music began in earnest with the Italian theorists only in the second half of the 16th century, and intensified as the century drew to a close, as shown by the magisterial survey by Palisca3. If “Renaissance” carries with it too much historical baggage to be misleading when used for the likes of Busnoys or Obrecht, is there another label which succinctly summarises the rich legacy of music between Du Fay and Willaert? Even if such a label exists, is it even useful?

Perhaps it is better to establish a time interval for our investigations without using a word which explicitly describes any perceived qualities of the music. Luckily, history abounds with coincidences and memorable signposts are plentiful. The beginning of the period is heralded by the decline of English influence on the continent as the Hundred Years’ War drew to a close in the West in tandem with the rising Ottoman threat in the East. The end of the period saw the cessation of the Italian wars, an extension of the Burgundian-French hostilities inherited by the house of Hapsburg which ended in Hapsburg-Spanish domination of Italy. Still, a title in the likes of “Music from the Battle of Varna to the Peace of Cateau-Cambresis” sounds far too unwieldy, and is presumptive in covering all the combination of both composed and improvised music and a good deal of pleasant noise besides. As Taruskin stated in his preface, his (and mine) work deals largely with literate music, music that is notated in physical form and can be reinvented even after all the singers have fallen silent4. This is the type of music cultivated by (invariably at this period) professional singers who read from choirbooks, manuscript partbooks, and, from 1501, printed music. Surviving exemplars of these tangible forms of music are the most prized treasures of the Western Literate tradition. They form the core of our knowledge about music then and it is thanks to their precarious survival that we need not stay silent today.

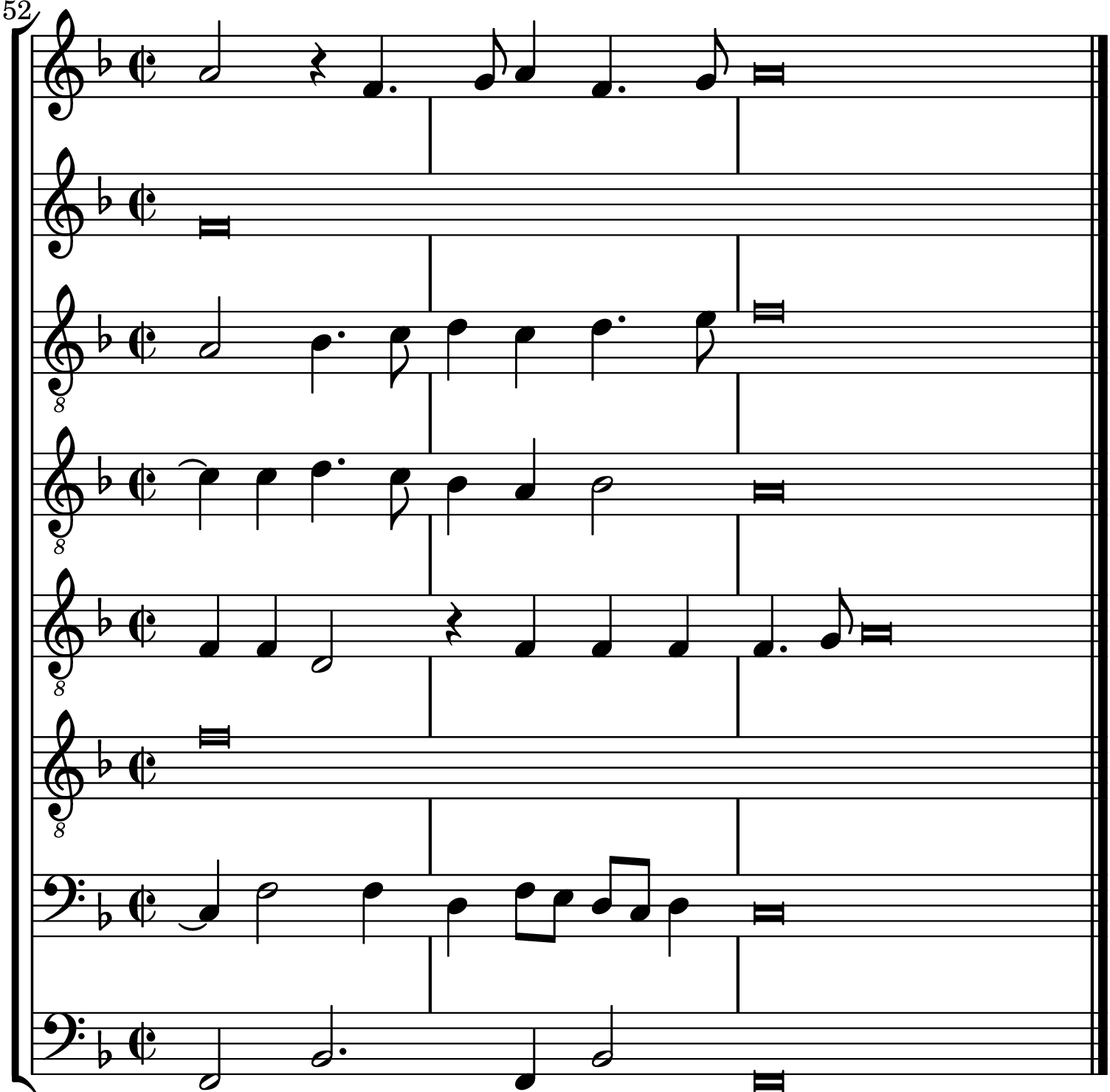

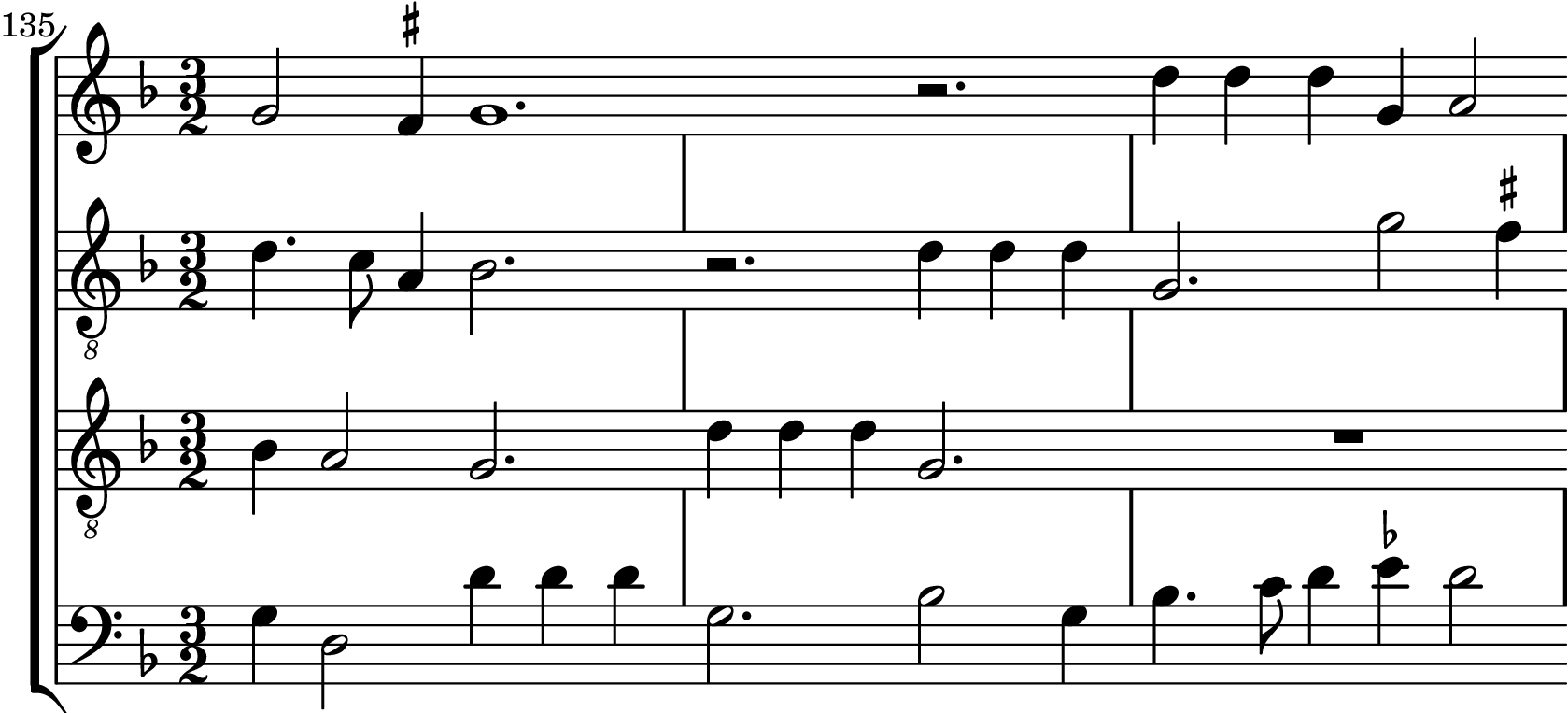

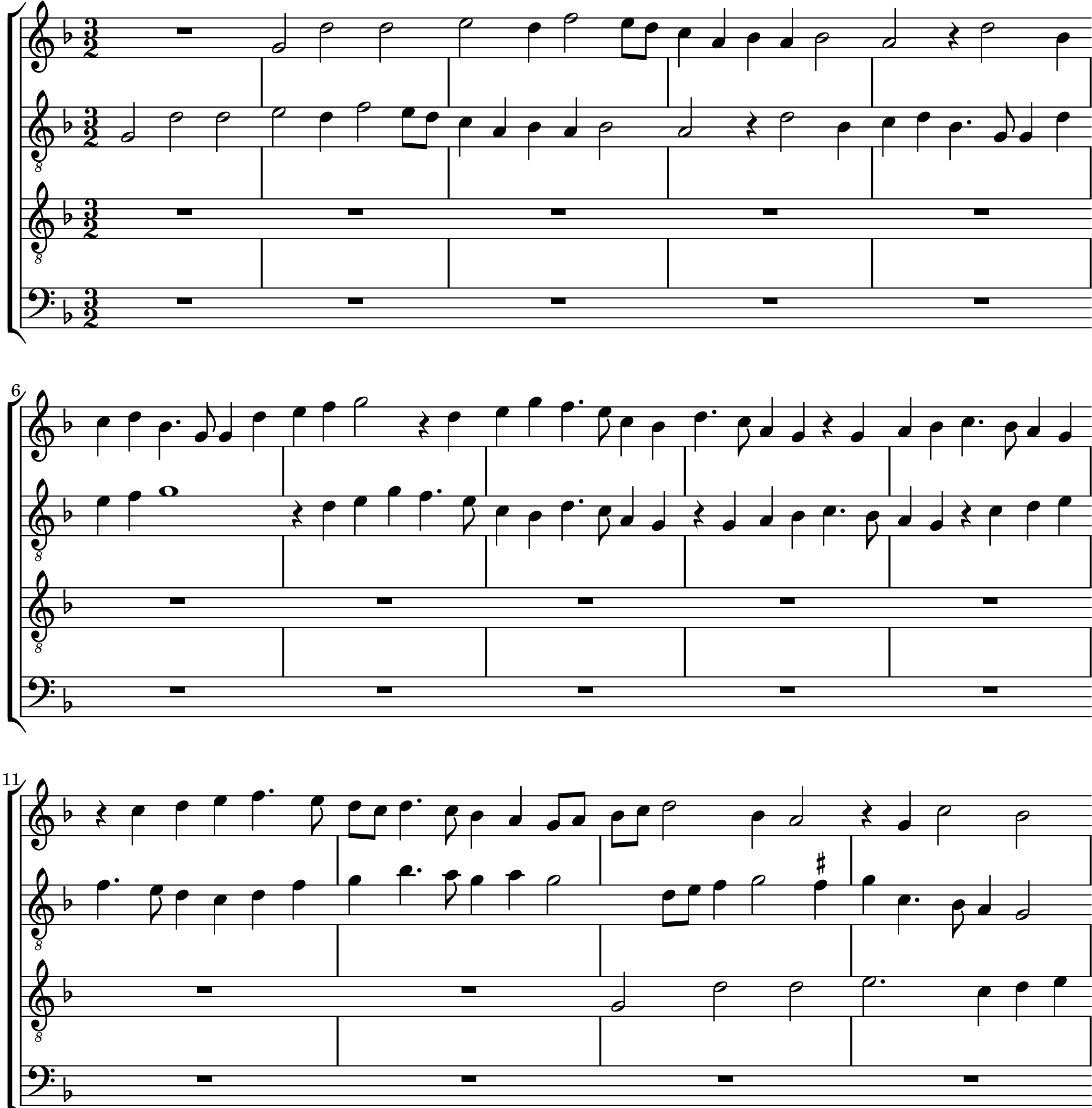

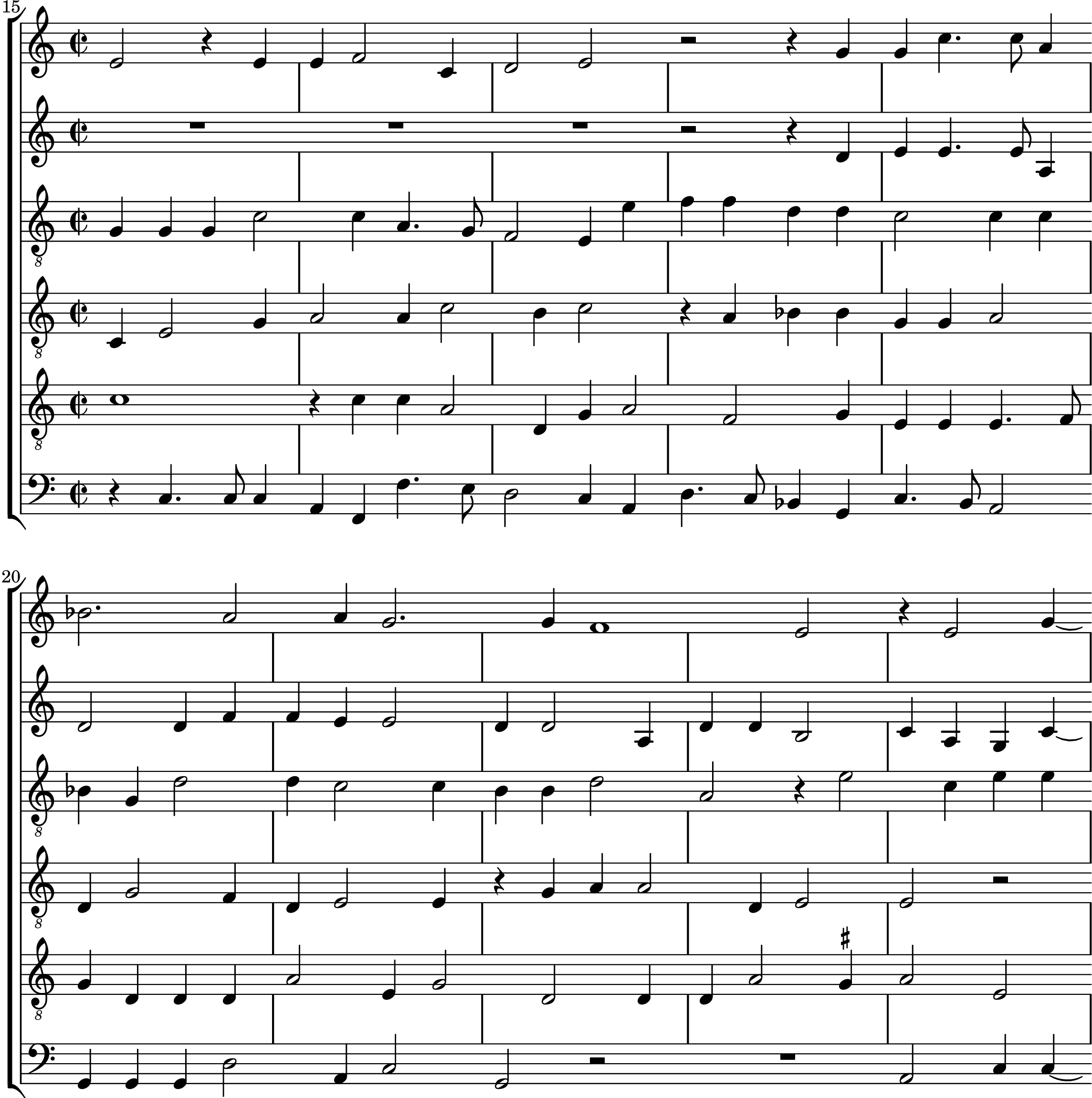

One clearly audible unifying feature of music from 1440 onwards is its sweetness. The proliferation of imperfect consonances, introduced by the English, produced music (to our ears at least) which is richer and more pleasant compared to the hollowness of the bare perfect consonances of the previous era. These bare intervals were initially relegated to the conclusion of pieces. Eventually, the expansion of triadic sonority continued until at the other end of our period, the love for rich harmonies began to outweigh the aversion for thirds in the final chord of the piece. The most succinct illustration of this progress can be found in a telling comparison between the endings of two masses both ending on F but separated chronologically by 100 years. Du Fay’s mass has the altus (second voice down) move down a third from A to F which creates the stark final sonority (Figure 1). Vaet’s mass is sumptuously scored for eight parts and his first tenor (fifth voice down) repeats Du Fay’s altus in reverse, moving from F to A (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Guillaume Du Fay, Missa Se la face ay pale, Agnus Dei III (ca. 1454) Click for audio.

Figure 2: Jacobus Vaet, Missa Ego flos campi, Agnus Dei (ca. 1566) Click for audio.

Apart from the coming of age of triadic harmony. There is also one other conspicuous feature which distinguishes this music from other periods. A great proportion of compositions have adopted melodies from elsewhere as a starting point in a method variously described as “borrowing” or “intertexuality”5. References to existing music are not rare in the Western Literate tradition, but it is during this time period that the obsession with reworking pre-existing music reached stratospheric heights and have not been surpassed since. The primary vehicle of such undertakings were the settings of the mass ordinary, which were usually the longest and grandest pieces of their time. But borrowing also seeped into the other genres such as the motet (through paraphrasing chant or incorporating secular melodies) and song (through combining secular melodies and latin chants). Viewed through the lens of 19th century Romanticism, the lack of originality in this period is indeed worryingly peculiar. However, the sophistication of the techniques of adapting the external material, which can be incorporated into the piece at several different levels, shows a genius which can only be describe as original.

Finally, the most obvious stylistic movement from the 1480s until the culmination in the 1540s is the increasing importance given to imitative counterpoint. Originally used as a hocket like device at the end of phrases. Josquin and his colleagues have augmented its importance by using it to organise the incipit of phrases. Josquin’s disciples further expanded its use until imitation became the only method to organise the macroscopic texture of the music. Imitative counterpoint permeated all the genres and created a peculiar homogenising influence which is most notable in the ars perfecta. By the time of Gombert and Willaert, a secular chanson can sound identical to a motet which in turn resembles the mass that parodies it, and madrigals can take on the weight and density of a motet. It is perhaps this highly unified musical landscape which spurred the innovations of the madrigal composers to break through and ultimately petrify the existing practice as a “classical style”.

Setting the Stage (1440-1480)

We begin in the mid 15th century with the handful of composers who were dubbed the “Tinctoris Five” for the distinction of being singled out for praise by the greatest musical theorist at the time6. Even though Modern audiences will probably only recognise Ockeghem and Busnoys among them, Regis, Caron and Faugues were all significant figures in their own right. The 1460s and 1470s were formative years in the tradition of western music, which origins can be traced back to the landing of the Caput mass by an anonymous English composer on the continent in the mid-1440s7. Complete settings of the mass ordinary existed before. Even the unification of all sections of the mass by a recurring cantus firmus have been tried in the prior decades by John Dunstable and Lionel Power (both of which, incidentally, have been put forward as possible candidates for the composer of the Caput mass), but the awe inspiring scope and revolutionary treatment of a low countertenor spurred the continentals to follow suit. The mass proceeded to occupy an important, if not central position in composition for the next half-century or so8.

In the 1450s only three continental masses achieved any great degree of circulation: Du Fay’s Missa Se la face ay pale on his own song, Ockeghem’s Missa Caput on the same tenor as the English mass, and Dormato’s Missa Spiritus Almus on another plainchant9. Ockeghem’s composition is exceptional even in the context of his own variegated output, and consequently a tough act to follow. The smooth lines of Du Fay and the clarity of his cantus firmus treatment make his mass the most palatable to modern ears, but its contemporary reception is much more lukewarm judging by its source transmission10. Dormato’s innovative use of mensural transformations of the tenor turned out to be the most influential, and he can count among his followers the likes of Busnoys and Obrecht who brought the development of strict cantus firmus manipulations to its apex.

Composers took up these innovations enthusiastically, and by the 1460s and 1470s there was a flowering of polyphonic masses composed all over the continent, and each preached their distinctive style. The aged Du Fay maintained the lucidity of his counterpoint to the end of his life, though with the Missa Ave Regina Caelorum, he pushed cantus firmus treatment to the boundary of paraphrase, an idea which was eagerly carried out by the younger generation11. What also flourished was the “L’homme arme” tradition, a series of cantus firmus masses fashioned on the catchy song with a strong link to the court of Burgundy. Begun by either Du Fay or Ockeghem in the early 1460s, the tradition became a testing ground for experimental techniques in both tenor manipulation, canon, and musical style. By the end of the 1510s it had generated at least 30 masses in the tradition12.

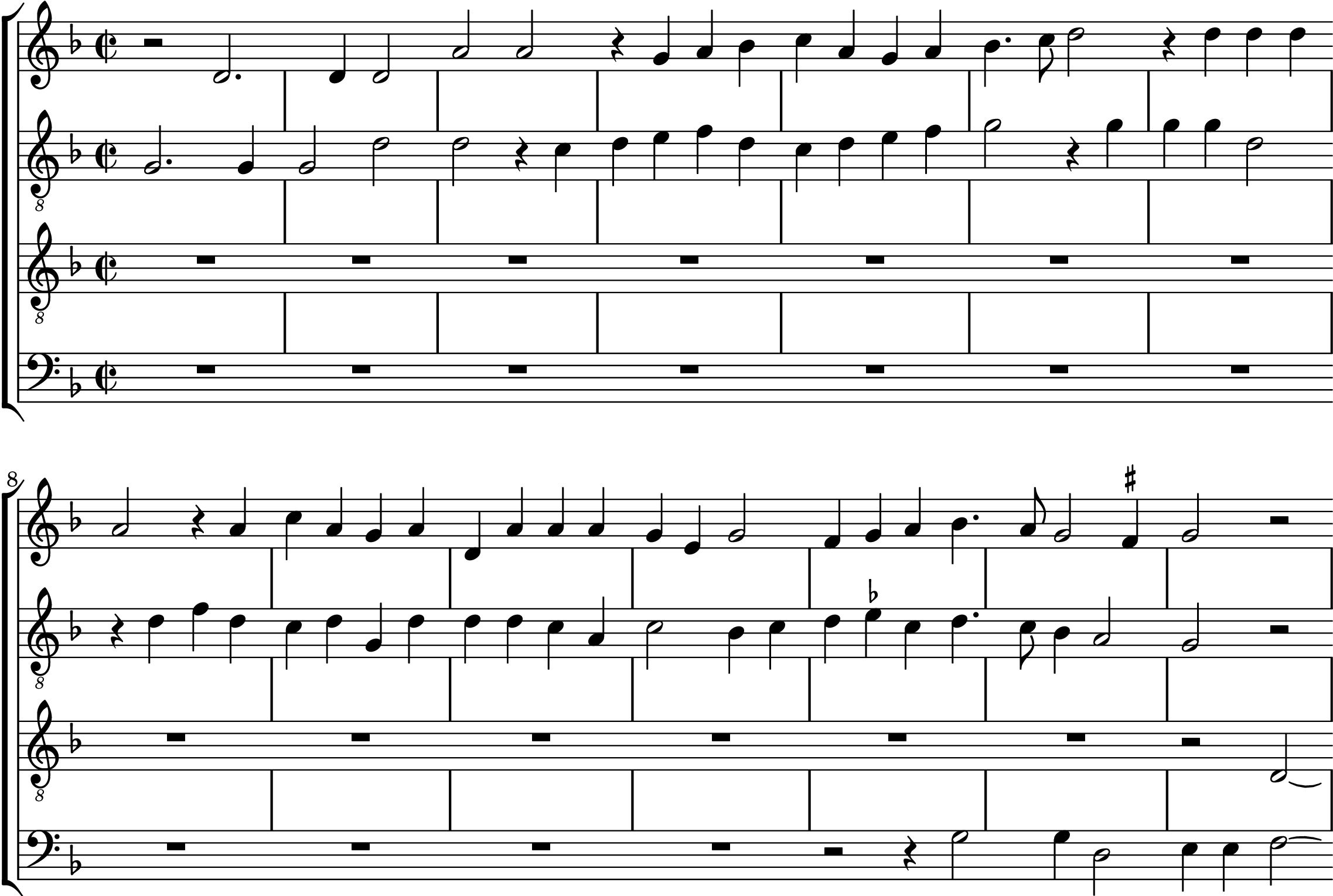

At the centre of this tradition stands the Missa L’homme Arme by Antoine Busnoys13. Although not a prolific composer for sacred music (he left only two masses and a handful of motets), Busnoys’s contribution to the “L’homme arme” tradition proved to be seminal. Unlike the music of his contemporaries, his music conveys great urgency and the melodies of the individual voices are lucid and focused. The mass radiates a sense of martial power that is unrivalled even in the “L’homme arme” tradition, most evident in the ending of Gloria which culminates in the falling-fifths trumpet call of “Doibt on doubter” rising through the voices in an act of defiance (Figure 3). There are also moments of great stillness where the tension mounts despite the stasis in the voices in the final Agnus Dei. In short, Busnoys was able to forcefully assert his music as a series of interconnected musical events, an unfolding process in which each moment has its own significance, as opposed to the continual unfolding of consonances in the greatest possible variety as preached by Tinctoris14. This change in attitude was absorbed by his younger contemporaries, most notably Obrecht, who carried it to its zenith in the decades following.

Figure 3: Antoine Busnoys, Missa L’homme arme, Tu Solus (ca. 1470) Click for audio.

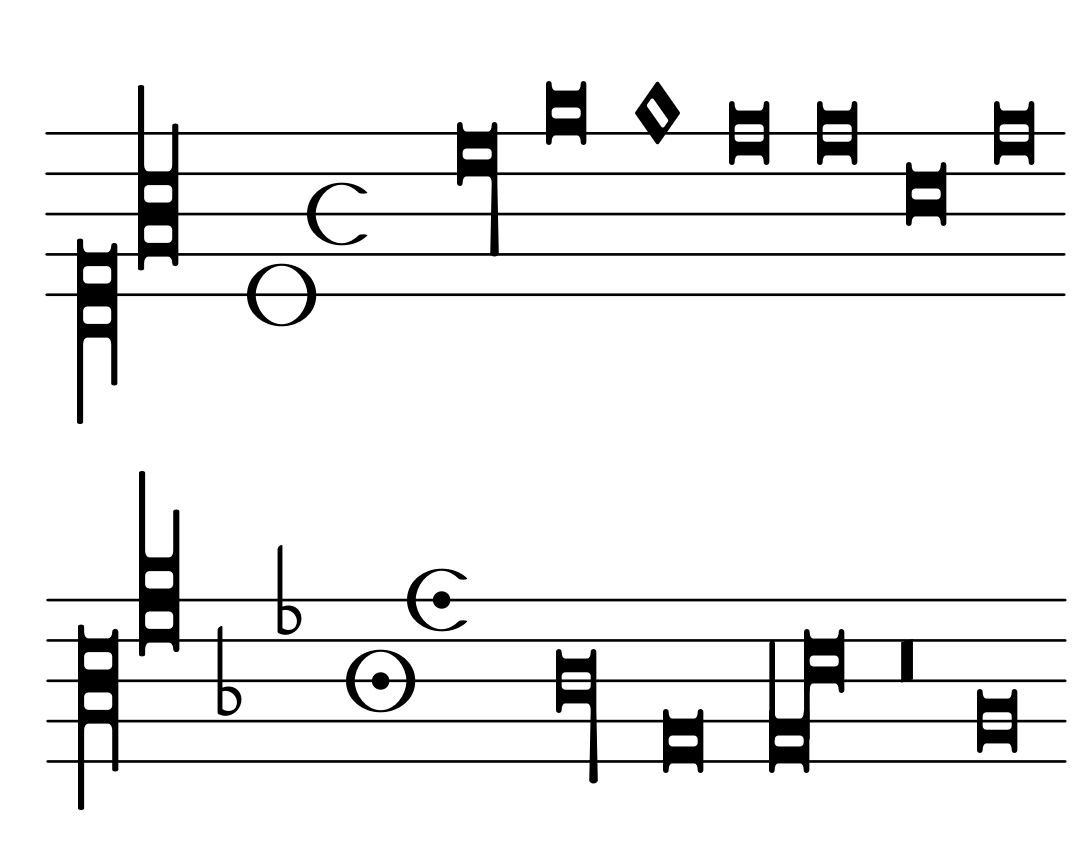

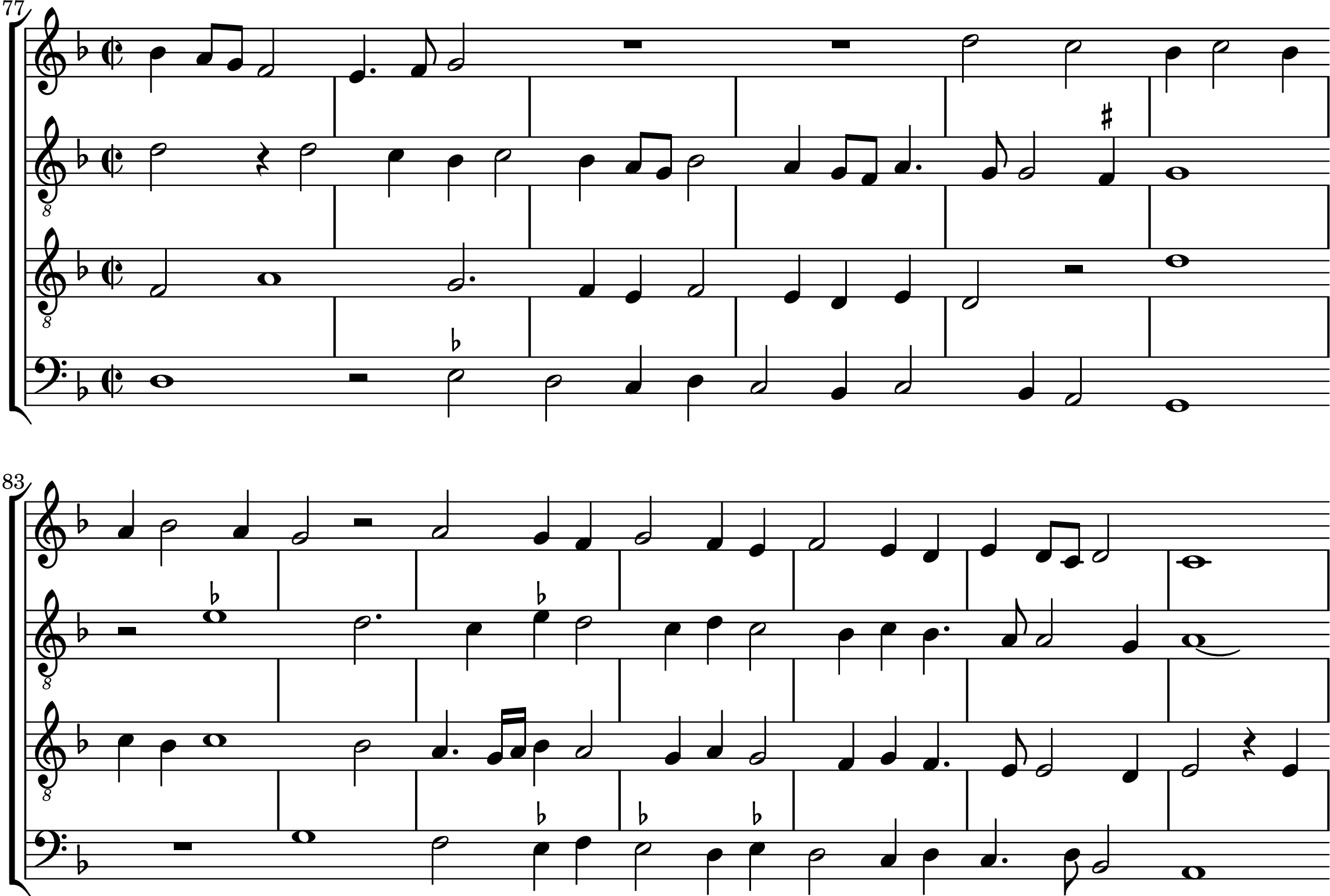

At the opposite of the very bombastic, public style of Busnoys stands the subtle, private world of Ockeghem15. Although the musical world of the two composers can’t be more different, they respected each other as professionals, if not friends. If one were to summarise the art of Ockeghem in one word, it would be concealment. Like Busnoys, Ockghem was clearly not satisfied with purely maintaining a shifting layer of consonances in the method of his contemporaries, but unlike Busnoys, the art of Ockeghem isn’t presented directly to the listener16. The most obvious example are his celebrated free masses, the canonic Missa Prolationum and catholic Missa Cuiusvis Toni where the craft of the composer is barely perceptible (if indeed it was perceived at all by anyone not singing from the notation, see Figure 4). Even in the other masses not constrained by so called “rational design”, Ockeghem has hidden structural devices such as imitation below the near impenetrable surface of the piece17. Some masses carry out a transformation before the very singer’s ears as the piece unfolds, such as his Missa L’homme Arme, where the sunny G mixolydian mode somewhat reminiscent of Du Fay changes imperceptibly over the mass, until finally in the third Agnus where the migration of the cantus firmus to the bass and the introduction of a signature flat in all voices changes the texture to an unmistakably Ockeghemian one18. The Kyrie-Gloria pair and the Credo of the Missa Fors Seulement might as well be composed by two different composers, or at least composed more than a decade apart. The strangeness and a feeling of unease in the Missa Ecce Ancilla Domini and Missa De Plus en Plus cannot be entirely attributed to its modal jungle and glacial harmonic movement either19. In short: “He was not a progressive, not a conservative, he was Ockeghem”20. Because of his idiosyncrasy and small output, Ockeghem’s influences are notoriously difficult to pin down, yet paradoxically he is also central to the canon (Molinet’s lament at his death mentions the leading musicians connected to the French court morning for him). What we do know is that five hundred years on, his music still fascinates (and puzzles) us.

Figure 4: Johannes Ockeghem, Missa Prolationum, Patrem. (ca. 1470?-1480?) The original notation from the Chigi codex indicates that four singing parts are produced out of the two notated parts, each singing part follows its own mensuration and clef. Click for audio.

The Greatest Generation (1480-1520)

Whatever the innovations of the previous two decades, by the 1480s a new generation of composers started to dominate the scene. The technical advancements of the existing compositions were absorbed, but the pieces themselves were rejected. Even a figure like Ockeghem is represented poorly in the surviving manuscripts21. What music were the scribes copying at this time? In a lot of the cases, the answer is Obrecht. A direct follower of the Dormato-Busnoys tradition, Jacob Obrecht emerged as the leading figure among the innovators22. In the early 1480s he managed to demonstrate his aptitude in the current style by writing masses which successively emulated of the styles of Busnoys (Missa Petrus Apostolus) and Ockeghem (Missa Sicut Spina Rosam). However he soon developed a intensely personal style that is based on a radical simplification of the texture of existing pieces. Despite (or perhaps because of) the strictness of Obrecht’s cantus firmus procedures, the music itself was direct, unpretentious and brimming with energy. Much of this was also thanks to greatly simplified modal-harmonic scheme of his music. Obrecht handled harmonic changes on a large scale with an uncannily prescient knowledge of harmonic function: he was able to create moments of great tension by moving away from the established modal centre in a highly articulated manner and dramatically veer back to generate spectacular resolutions. This provided long range coherence on top of the small scale drive of Busnoys, and Obrecht was able to routinely create longer pieces which retained the energy of Busnoys at much a larger scale. Obrecht’s music is music that went places. It has a narrative and a dramatic course of action which is absent in the music of the preceding years which seem to dwell on the sheer sweetness of consonances of the moment and paid little thought to the rest of the piece.

Obrecht’s pioneering efforts were followed immediately by his contemporaries, chief among them Josquin, who had scarcely made a name by himself while Obrecht had already finished composing his mature masses in the early 1490s. Josquin’s innovations started with his motet Ave Maria… Virgo Serenata of 1485, where, like Obrecht, he broke from the sinuous lines and indifference to text of the motet writing of the past23. The text is presented in a kaleidoscopic fashion with a flurry of devices: imitation, chordal harmony, contrast of voice pairs, close canon. Together they all conspired to present text in the most effective manner. Josquin proceeded to learn from Marbrian de Orto, his colleague at the Sistine Chapel during his stay at Rome24. Orto’s masses instructed Josquin in how to handle the long range organisation of material that was so crucial to his musical thinking, and it is not surprising that two of his masses produced in this period, the Missa ad Fugam and Missa L’homme arme super voces musicales respond directly to Orto’s masses. In these pieces Josquin embraced the strict procedure of canon, which has been largely neglected by Obrecht. The super voces mass also injected new energy into the L’homme arme tradition by its daring presentation of the complete tune on all notes of the hexachord, while maintaining a D mode throughout in the other voice. More than anyone, Josquin realised the importance of providing a satisfying conclusion to his mass, and his Agnus Dei settings are consequently some of the most elaborate of the cycle. In the super voces mass this high point occurs at the literal culmination of the cantus firmus, which has migrated from the bottom of the tenor range to the superius. It is also sung at quadruple augmentation while the voices below furnish a series of breathtaking close imitation which brings the music to a close (Figure 5). Busnoys was able to generate bursts of energy, Josquin showed us how to sustain that energy for over 120 bars.

Figure 5: Josquin des Prez, Missa L’homme Arme Super Voces Musicales, Agnus Dei III, (ca. 1490?-1495?). Click for audio.

In addition to Josquin, two other musicians made their first appearance on the musical landscape in 1492, both of whom are associated with the Hapsburg court. Pierre de La Rue of Coutrai, who was slightly younger than Josquin, was anxious about the influence of the master and felt a need to compete, even if the competition was one-sided25. His Missa L’homme arme (I) contains sections which are not just modelled on but also attempts to one-up Josquin’s work, including three mensuration canons in the Kyrie, and a 4-ex-1 proportional/mensuration canon as the second Agnus. The latter being an clear homage to the 3-ex-1 Trinitas canon of Josquin’s super voces mass. (There is also a 3-ex-1 modally ambiguous canon in La Rue’s much later Missa Sancta Dei Genitrix, a homage to Ockeghem’s famous Prenez sur moy canon.) Moreover, the transposition of the L’homme arme melody in Josquin’s original now permeates the whole work, and La Rue states it on every possible starting note, and combines them in close imitation. Hardly any section of the mass goes by without simultaneous statement of paraphrase of the melody on two different keys. The most remarkable section is undoubtedly the first Agnus, where the tune is present more or less complete in a imitation at the lower seventh, stated successively on D - E - F. The L’homme arme melody with its horn calls of a leap of fifth pull extremely strongly towards its modal final, and the simultaneous juxtaposition of it on three different notes at times threaten to tear the music apart, but La Rue managed to balance it on a knife-edge and the resulting tension is exhilarating to behold (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Pierre de La Rue, Missa L’homme Arme I, Agnus Dei I, (ca. 1490s?). Click for audio.

La Rue’s L’homme arme mass might be an aberrant juvenilia, its counterpoint is often awkward, and its melodic invention sparse due to the ubiquity of the L’homme arme tune in all voices. La Rue quickly settled into a more classical, balanced and smooth style of voice leading. His Missa Ave Maria clearly reflect the influence of Josquin’s paraphrase masses, such as the use of imitation duos and the frequent fore-imitation of the tenor melody in other voices. However the voices are much more relaxed than the energetic counterpart in Josquin. Exceptionally for the period (though not in La Rue’s oeuvre), the Credo alone expands to five voices. The employment of more than four voices also became first consistently realised in the compositions of La Rue, who wrote more five voice masses than any of his contemporaries26. He was also among the first to consistently borrow from multiple voices of a polyphonic composition while rejecting the existing simple cantus firmus principle. The modern term given to this is either “imitation” or “parody”, and it is a much more sophisticated method of musical borrowing than using one external melody as a structural scaffolding for the mass. This was a step that neither Josquin nor Obrecht, his two most significant contemporaries were willing or able to take.

Like Josquin, and unlike Obrecht, the Netherlandish art of composing canons also fascinated La Rue, and he composed four canonic masses, more than any of his peers (and only one fewer than Palestrina, whose five canonic masses makes up a much smaller proportion of his entire mass output): Missa L’homme Arme (II), Missa Incessament, Missa Ave Sanctissima Maria and Missa O Salutaris Hostia. The latter two are wholly canonic, with no free voices. With the exception of the second L’homme arme mass, the three other canonic masses are all based on polyphonic models. They combine canonic techniques and polyphonic borrowing (if indeed the O Salutaris Hostia is based on a now lost model) with increasing sophistication:

- Missa Incessament: for five voices, 2-ex-1 canon in the lowest two voices

- Missa Ave Sanctissima Maria: for six voices, 6-ex-3 canon

- Missa O Salutaris Hostia: for four voices, 4-ex-1 canon

It is truly astounding that the entirety of the O Salutaris Hostia mass is generated by a single voice, and this striking economy is immediately visible in its appearance in Antico’s 1515 publication, where only one voice is notated and the entire mass fits inside six pages as opposed to the nearly 30 pages that Josquin’s Lady Mass takes up27.

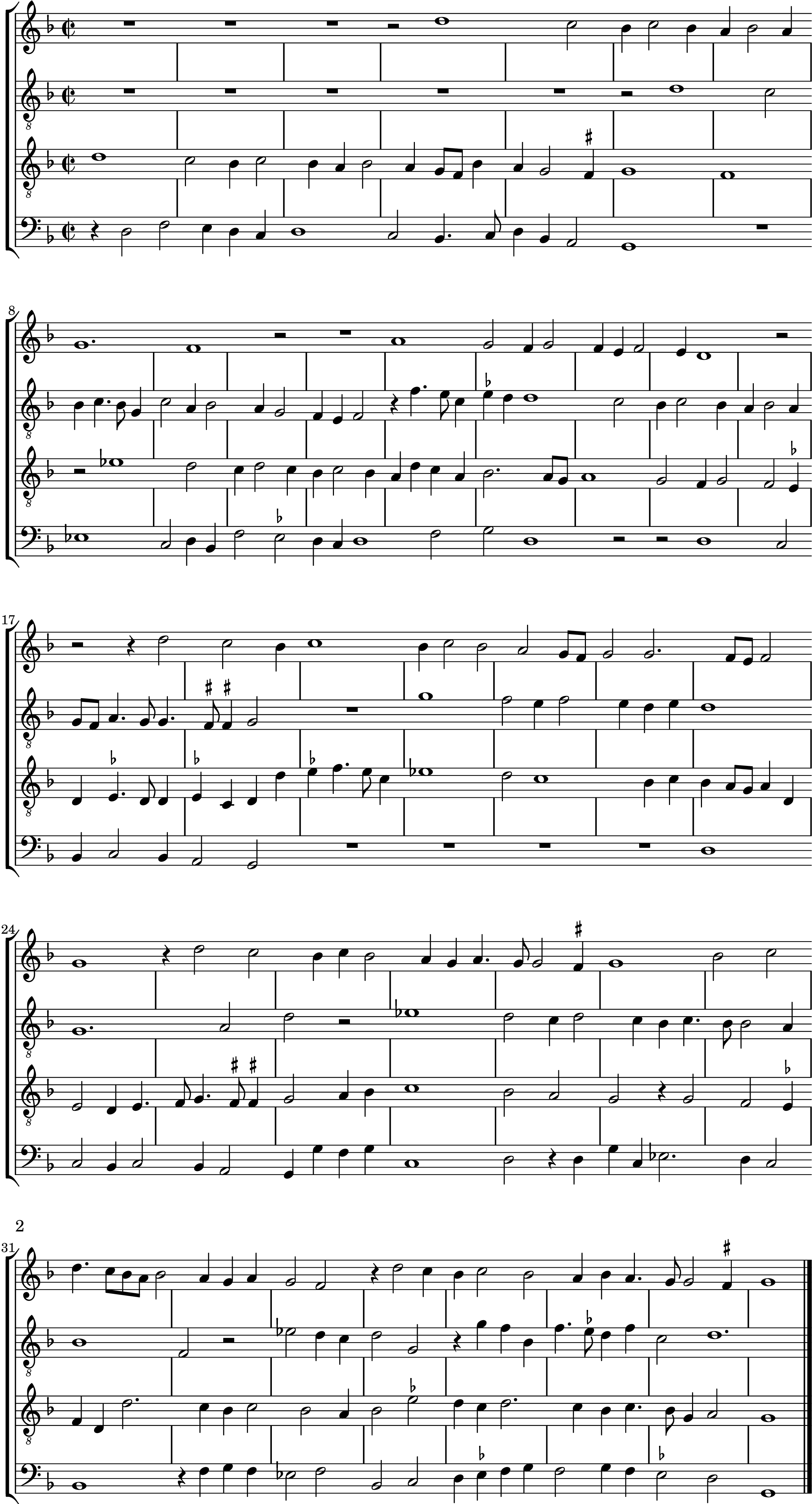

If La Rue inherited Ockeghem’s gravitas and canonic art, then Agricola inherited the elder composer’s fantasy and elusiveness28. Agricola’s surface style betrays the influence of his own generation, with the predilection for paired imitation and generally thinner texture than that of the preceding generation. Like Obrecht, his melodies are noticeably more energetic than the preceding generation, and as a rule the beginnings of musical segments are organised by imitation. Yet in marked contrast to Obrecht’s use of the procedure, where these elements are carried out in a straightforward manner and unfolds in well defined sections building up and winding down a musical narrative, Agricola’s voices are unruly, and frequently embark on incredible flights of fancy. Much like Ockeghem’s music, it can only be successfully described in negative terms: anti-rational, irregular, directionless. Generations of writers had noted this almost Baroque sensibility in this fifteenth century composer, though his style perhaps carries more vestiges of the previous generation than it heralds the mannerisms of an age yet to come29. A typical example of his playfulness can be seen in the opening of his Salve Regina, where the tenor’s strange three crotchet sequence stubbornly refuses to match up with the superius (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Alexander Agricola, Salve Regina I. Click for audio.

Nevertheless, Agricola’s genius is most apparent when he worked on the largest scale, and his chanson based masses are among the lengthiest of its time. The Missa In Myne Sin in particular, possibly his finest cycle, extends to well over 1000 bars even in its current decapitated state. In these late masses we can see the free school of cantus firmus treatment reaching its zenith, just as Obrecht perfected the strict school of cantus firmus treatment. The references to the original chanson are cast far and wide, with fragments coming and going with no apparent order. Sudden explosions of action can abruptly dissolve, without warning or reason, into sections of extreme stillness. Tellingly, the only complete statement of the unembellished cantus firmus appear in the tenor at the junction between the two usually disjoint sections of Benedictus and Osanna. It is surely an irony of fate that Agricola and La Rue, two powerful musical personalities who are almost exact opposites, worked as colleagues for more than a decade. Nonetheless, Agricola’s style may have influenced even Obrecht, the rational, straightforward composer par excellence. In Obrecht’s last mass, the Missa Maria Zart, several stylistic and structural homages point unmistakeably to Agricola and his In Myne Zyn mass30. Obrecht’s music took on a more meandering, aimless characteristic, the different sections of the liturgy also grew to excessive lengths with the addition of tenorless duets and trios in the middle of the Credo and Gloria, a feature of the In Myne Zyn mass which does not occur in Obrecht’s previous works. The rhythmic wizardry in the Agnus also echoes a similar section in Agricola’s mass. Fittingly, both musicians died within an year of each other in foreign lands. Their deaths silenced two of the most prominent voices of their time, and one could only speculate at how the two would react to the rapidly changing musical landscape in the second and third decades of the 16th century.

Another importance circle of composers, which may be considered the direct successors to Ockeghem, was centred around the French court. Their leader was Jean Mouton, who was perhaps the most successful follower in Josquin’s footsteps. In his motets and masses, Mouton showed all the preoccupation with text and structural clarity that characterised Josquin’s best works, thought he moderated them with a smoothness that is more characteristic of La Rue. His compatriot Brumel, who succeeded Obrecht at Ferrara, followed his predecessor more clearly and generates much more raw energy. Though he is not averse to ostinato techniques to achieve the most striking effects. The brothers Fevin were also important figures in the development of the imitation mass, in particular the technique of polyphonic borrowing. Their debt to Josquin is often made rather explicit: Antoine wrote a mass on Josquin’s most famous motet, Ave Maria… virgo serena, and Robert wrote a Missa La Sol Mi Fa Re, a cheeky reference to one of Josquin’s most sublime masses. Both of these compositions reworked Josquin’s ideas with subtlety and intelligence. Robert in particular was even able to create passages with obsessive repetition, a hallmark Josquinian mannerism, and produce pastiche which is almost indistinguishable from genuine Josquin (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Antoine de Fevin, Missa La Sol Mi Fa Re, Kyrie II, (ca. 1515). Click for audio.

Pervasive Imitation (1520-1560)

Josquin and Obrecht were part of the first boom generation in literate music. For the first in the West there was more than just a handful of major composers active at the same time. By cultivating their own distinctive personal style, there was also more variety than ever in the music scene. However, when the era ended with Josquin’s death in 1521 the younger generation of composers were ready to swing the stylistic pendulum firmly back in the other direction.

It is tantalising that we know so frustrating little about the composers born in the 1480s who took over immediately following Josquin’s death. We do know that they were the first to enjoy the proliferation of music printing as soon as they reached musical maturity, and their compositions were rapidly taken up by the presses alongside compositions of the old masters. There are names that reoccur frequently in Attaignant’s motet prints: the Frenchmen Verdelot, Gascogne and Moulu, and the Flemings Bauldeweyn, Richafort and Appenzeller31. Initially, they followed the spirit of the previous style, one that focused on intelligibility and sharply delineated music phrases, but with more emphasis on smoothness and continuity. Eventually this focus on an unbroken strand of music from beginning to end established itself as the only (and classical) style of vocal polyphony. The effective declamation of text, a hallmark of the previous style and one which Josquin excelled at, fell by the wayside. Nevertheless, in the immediate years following Josquin’s death, the difference was subtle, and many of their compositions bear mixed attributions to older composers, particularly Josquin, whose reputation enjoyed an ever upwards trajectory in the first century following his death. Moulu’s Missa Missus est Gabriel Angelus (Figure 10), which is based on Josquin’s motet, is a virtual twin of the mature Josquin . A comparison of the opening duet in the Gloria of Moulu’s mass with Josquin’s Missa Ave Maris Stella (Figure 9) makes clear the obvious similarity in structure, modal treatment and also sense of phrasing between the two masses.

Figure 9: Josquin des Prez, Missa Ave Maris Stella, Et in terra, (ca. 1490s?). Click for audio.

Figure 10: Pierre Moulu, Missa Missus est Gabriel Angelus, Et in terra, (ca. 1510s?). Click for audio.

The style of the mass changed drastically in the 1530s, when an entirely new principle of organisation took over. Although the mass has always depended on external material such as chants (unrelated to the chants of the mass itself) and secular tunes both monophonic and polyphonic, it has always maintained a soundscape which is distinct from its model throughout the late 15th century and into the opening years of the 16th century. A typical mass of the second half of the 15th century would borrow from a specific secular chanson, and though the borrowing is nowhere near as strictly confined to one voice (usually the tenor) as we once thought32, the long, melismatic and irregular melody lines of the mass differed in quality with the short, tuneful and regular phrases of the formes fixes songs. The construction of such a mass is inherently a destructive process, where the tenor of the original chanson is removed from its surroundings and placed in a foreign body, and often stretched on the mensural rack or chopped up into little pieces until it hardly bears any resemblance to the original. New lines of counterpoint were then fashioned for it which, though they may fleetingly reference the original, generally constitute an entirely different soundscape. What’s more, the delicate phrase structure and repetition scheme of the formes fixes chansons are swept aside. Since the borrowed tune is usually transformed into a slow moving structural backbone hidden among the inner voices, even connoisseurs who are familiar the tune have difficulty recognising it while listening.

This attitude changed with the Greatest Generation. Leading the charge, as usual, was Jacob Obrecht with his segmentation masses. Whereas in the Missa Rose Playsante references to the original chanson outside the tenor are somewhat frequent, in the Missa Je ne demande the presence of Busnoys original is pervasive, and we find entire blocks of polyphony take wholesale out of the original chanson. By the time Obrecht wrote his Missa Malheur me bat, he had learnt to integrate this extensive polyphonic borrowing with ever more tightly into the musical narrative of the mass. Here direct quotations of the chanson tenor lasting tens of bars at a time both act as a culmination leading up to the introduction of the cantus firmus and glue subsequent cantus firmus statements together (Figure 11). Nevertheless harmonically the mass is firmly anchored in A, which a modal area is never explored in the original chanson. In the next mass, Missa Si dedero, based on an original by Agricola, Obrecht went further than any of his previous efforts. Not only do melodic quotations appear simultaneously in all voices, they occur throughout the length of movements, and even the “free” segments without direct quotations are infused with the kind of nervous energy that permeates the writing of Agricola’s original. Imitating Agricola was not without costs, and the forward momentum of the musical narrative, which was the trademark of the Obrecht’s mature style, suffered. Nevertheless, one can feel that Obrecht is no longer satisfied with simply adapting the source material as a scaffolding melody and subsuming it under his style, he yearned for ever tighter integration between all the voice parts. In the final stages of his musical development, Obrecht decided that the occasional nod to the original in the free voices no longer suffices, but the overall style and atmosphere of the original piece should be replicated. In short, the mass needed to imitate its model.

Figure 11: Jacob Obrecht, Missa Malheur me bat, Qui Tollis, (ca. 1497?). The bass presents the tenor of the original chanson, transposed down a fifth, between two cantus firmus statements in the superius. Click for audio.

Frustratingly, Obrecht’s life was cut short right at the cusp of this stylistic revolution. This change in musical philosophy also coincided with the end of interest for the medieval formes fixes poetry which has inspired composers since Machaut. The chanson models of Obrecht’s segmentation masses were at least one or several decades old, and soon after his death both formes fixes chansons and cantus firmus chanson masses faded into obscurity.

What replaced chansons as the primary model for masses was the new motet. The change was initiated by composers of the French orbit, Mouton and Divitis, and, if we were to believe authenticity of the Missa Mater Patris and Missa Quem Dicunt Homines, Josquin himself33. The motet Quem Dicunt Homines by the young Richafort became an instant classic and remained as a source for masses until the end of the century. At the beginning of the century it must have been groundbreaking, since the music was based on an entirely modern style which moderated the austere alternating duets of Josquin with richer texture supported by more frequently use of imitation in all voices. It would make no sense to write a mass on it by isolating a single structural voice and treat it in the old cantus firmus fashion. Not only would there be an inordinate amount of rests, but the short, stereotyped phrases would prove dull compared to the long, graceful and rhythmically interesting melodies of the older chansons. The only way forward was to move away from merely copying the contours of a single melody and to borrow in a structural manner. As a consequence, the mass began to imitate the model, its soundscape, mode and structure. The procedure of musical borrowing became more sophisticated as it grew to encompass several different levels of the musical organisation. In addition to quotation of isolated melodic fragments of the model, mass composers now also borrowed the arrangement between the voices in each imitative section. On a larger scale, the order of the entries of each melodic idea also became important, they could be followed more or less strictly, or altered at will to better suit the words of the mass text or the structure of the newly composed section. The composer may have taken the original apart as he pondered its potential, but when he reassembled the fragments into his own piece he made sure that it bore a strong resemblance to the original. This procedure is no longer as destructive as the old cantus firmus technique, but rather regenerative: it affirms the existence of the original inside the imitation, and offers a complementary interpretation of the former without overwhelming it with new meaning. The connection between the source and model became tighter than ever, and this contributed to the merging of the soundscape of the mass and its source material. In the fifteenth century the style of a mass betrayed the composer’s own personal stamp, but in the sixteenth century the style of a mass demonstrates more than anything the traits and qualities of the source material.

What made this possible was the establishment of imitation as the standard technique for the local organisation of all the voices. Again, this is not an entirely new development, since the use of repeating melodic ideas in each voice as they are introduced can be traced all the way back to the beginning of the 15th century34. Initially, imitation was used only sporadically but with increasing frequency from the 1480s onwards, and even as elusive a composer as Ockeghem has cleverly hidden structural imitation strewn throughout his works. Once Busnoys realise its powerful organisational potential in his L’homme Arme mass, Josquin and Obrecht were able to establish it as a standard part of musical syntax. But this still wasn’t enough for their successors, who saw imitation as more than a tool merely used to signpost and tie together the beginning of sections. In their hands, imitation became syntactic and pervasive. The class of 1480 lead the way for this transition, and class of 1500 brought it to its apotheosis. The latter generation’s works start to appear in the late 1520s, and by the late 1530s they have completely dominated the printing market in scared music. At the head of this tradition stands Nicolas Gombert, who spent his best years as master of the choirboys for the imperial chapel35. Gombert’s works demonstrate the high degree of homogeneity of music typical of his generation, his chansons, motet and masses are dominated by a common aesthetic goal: an unbroken flow of imitative counterpoint in all voices with essentially no change of texture. Particular striking are his 5 and 6 voice motets, where the frantic activity in all voices creates a constant passing dissonance that prevails on every beat. Gombert also relaxed the strictness of the imitation, and shortened subjects to small stereotyped cells so that entries can be maximally overlapped, and a full exposition in six voices may last little more than three breves in imperfect time. All these striking features are demonstrated by his six voiced Missa Quam Pulchra Es which is loosely based on the synonymous motet by Bauldeweyn (Figure 12). Bauldeweyn’s motet is a clear example of austerity and lucidity of the medium so characteristic of Josquin, and he himself also wrote a six voiced mass based on the same motet where he had carefully enlarged the scope of his motet while maintaining its delicate balance of imitative duets and trios alternating with rare sections of full scoring. Gombert’s borrowing technique in this case is as elusive as Ockeghem’s in Missa Au Travail Suis: the first theme of Bauldeweyn’s motet opens every major section but references to the motet disappears almost completely afterwards, and Gombert unfolds his own themes in his usual pace. The French printer Attaingnant had printed this mass a little more than 10 years after the death of Josquin, who was supposedly Gombert’s mentor. Yet Gombert and his contemporaries’ concentrated style are so at odds with Josquin’s aesthetic that they seem to be reacting against Josquin’s influence. Indeed, printed alongside Gombert’s mass in the very same volume was a Requiem by Richafort which very explicitly pays tribute to Josquin himself. Apparently Gombert’s generation had no trouble exalting Josquin the man while simultaneously ignoring the path tread by Josquin the musician.

Figure 12: Nicolas Gombert, Missa Quam pulchra es, Patrem, (before 1532). Click for audio.

There were also other major figures serving alongside Gombert colleagues in the imperial chapel, the more productive (at least judging by their surviving oeuvre) being Thomas Crecquillon and Pierre de Manchicourt. Crecquillon produced mainly chansons and motets, Manchicourt masses. Both also favoured the thick imitative texture with that is a hallmark of this generation, but tempered it with a degree of moderation and treated it less intensely as Gombert. The difference however is subtle and even scholars struggle with the case of conflicting attributions in this era, particularly cases concerning Crecquillon and his northern compatriot, Jacob Clemens non Papa36. Clemens was one of the most productive motet writers of all time and in a productive career that lasted not more than 15 years, he composed just over 230 motets37. This compares favourably with the output of Lassus and Palestrina, both of whom were active for more than 40 years and count among the most prolific motet writers of all time. Yet even printers who dealt regularly with this music had trouble telling apart Clemens and Crecquillon, something which is unthinkable during the era of distinct musical personalities just a few decades back (no work of Obrecht, for example, shares an attribution to Josquin and vice versa). What we can establish is that this style of writing certainly crossed national boundaries (Clemens was active in the Low Countries, while Crecquillon worked in Spain), and the most profound writer of masses of their generation was in fact Cristobal de Morales, a native of Spain.

Morales must have had spent his formative years absorbing the music of Josquin, for he was the composer who most conspicuously displayed his allegiance to the venerated elder composer38. This is shown in the choice of models for his masses: two on the venerated L’homme arme melody, one of them with the tune stated on F, exactly as Josquin had; a mass on the hymn Ave Maris Stella which extended Josquin’s canonic procedure in one section to the entire mass; a mass which puts the superius of Josquin’s chanson Mille Regretz into the top voice, and accompanies it with smooth counterpoint in the five voices below. This last mass is especially fascinating since its Sanctus and Agnus Dei exists in different versions, and the unpublished version preserved in the Vatican Library cites the final motif of Josquin’s Pange Linga mass in its poignant closing moments. This unmistakable homage is further reinforced by the fact that both Morales and Josquin served in the Papal Chapel. Morales’ debt to Josquin however runs deeper. Although he composed in the continuous imitative idiom of his contemporaries, he was always willing to sacrifice homogeneity for dramatic emphasis. His harmonies are also purged of the excessive dissonances of his northern colleagues, and point towards a purity of treatment that became a model for Palestrina, who based two of his own masses on motets by Morales. Morales’s reputation was international, and his compositions were featured in the Venetian printing presses as early as 154139. His most popular work was the collection of magnificat settings in all eight tones. Morales set both the even and odd verses to polyphony, which was how they were sung in the Papal Chapel. However, the magnificats were mutilated when they were published. Since everyone other than the Pope’s singers sang either the odd or even verse, the magnificats were published with the verses separate. Despite this musical transgression, these magnificats underwent a truly spectacular publishing history. They were reprinted at least fourteen times by the end of the century and disseminated well into the 18th century. The enduring popularity of Morales’s magnificats dwarfed magnificat settings by any other composer from the sixteenth century, and such popularity seems well deserving judging from the consistency of Morales’s modal practice, the serenity of his voice leading, the ever presence of the magnificat tone, and the eminently singable lines.

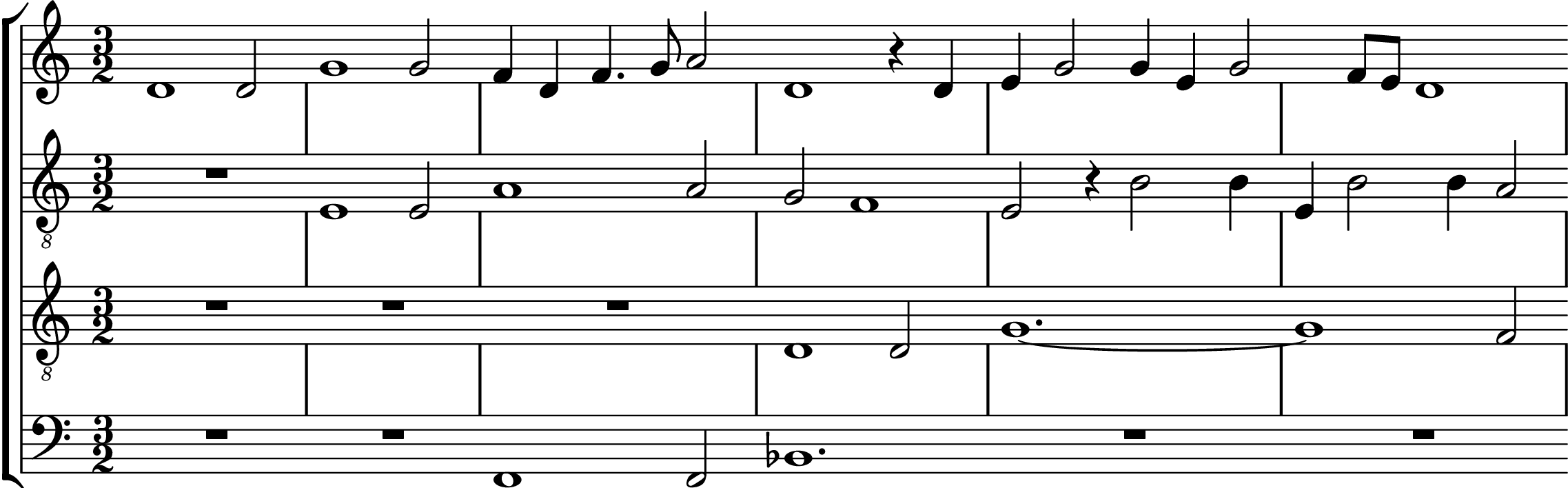

As impressive as the magnificats are, they were not Morales’s greatest publication. In 1544, Morales supervised the publication of two sumptuous volume of sixteen masses in choirbook format. Publication of masses was less common than that of motets, and publication in a lavish upright folio format was practically unheard of. Morales was certainly the only one of his generation to have personally overseen the editing and publication of his masses. The layout followed that of an anthology of masses brought out by Antico 30 years ago, and it was again taken up by Palestrina in his second book of masses. Morales selected works that would best represent the breadth and confidence he had in the art of mass composition: cantus firmus masses stand alongside paraphrase and canonic masses, but most importantly they were crowned by a series of imitation masses which exceeded any previous masses in the sophistication of their borrowing techniques. There were four for four voices, two for five voices, and one for six voices. Together they seemed to sum up the possibility for parody for all the common combination of voices and modes. All of them share a consistency of method in treating the borrowed material, in addition to structural similarities. In particular there is a common thread that runs through the four voiced Missa Aspice Domine, five voiced Missa Quaeramus Cum Pastoribus and six voiced Missa Si Bona Suscepimus. The long, weighty first subjects of the model motets were used not only as the beginning off every major section (or in the Si Bona Suscepimus mass’s case, every minor section as well), their length and memorability allow Morales to use them as signpost of structural events within the mass. No less astonishing is the variety of countersubject fashioned against them, original or otherwise. The Kyries in particular show an incredible sensitivity to the model, where material are presented strictly in the order of their presentation in the source motets. However the counterpoint and imitative entries may be vastly different. An example can be found in the Aspice Domine mass, where wittily Morales presented the second subject on “Quia facta est” before the first subject on “Aspice Domine”, turning established parody techniques on its head. The bass in this section states nothing but repetitions of these two themes. In the other sections, by varying the number of themes presented and the length of their presentation, Morales was able to achieve dramatic articulation. The following Christe, roughly the same length as the proceeding Kyrie, goes through four themes. The presentation of the first theme is contracted (14 bars in the original versus 8 bars in the mass), but the second theme, a tortured 7-6 suspension lasting 8 bars in the original, has the order of the entries reversed but the length preserved. The greater relative length given to the second theme is Morales’s subtle way of emphasising this particular section. This procedure is brought to its conclusion in the second Kyrie (Figure 14), where Morales has restricted himself to a single theme: an extremely awkward syncopated scalewise descent which forms jarring suspensions with its countersubject (Figure 13). This almost entirely undistinguished theme was used by Gombert as a bridge between the previous and the penultimate theme, here in the mass is stretched out to fill the length of the entire second Kyrie, a section three time its original length. Yet it is precisely the obsessive repetition of such an awkward theme that lends the music a poignancy which rivals or even surpasses the desolate, penitential atmosphere of the motet. The end result is music which is recognisably Gombert, yet unmistakably Morales.

Figure 13: Nicolas Gombert, Aspice Domine, Part 1, (before 1532). Click for audio.

Figure 14: Cristobal de Morales, Missa Aspice Domine, Kyrie II, (1544). Click for audio.

Elsewhere on the continent, musicians from the low countries still dominated the musical scene. In the north, even minor figures such as Lupus Hellinck and Johannes Lupi were esteemed long after their deaths, judging by the popularity of their motets as models for later composers. The situation is much the same in Italy, where musicians from north of the Alps filled the most prestigious positions in the courts and churches. The Frenchmen Arcadelt, Jacquet of Berchem and Lheritier enjoyed tenure in Rome, Jacquet of Mantua was patronised by the Gonzagas in the eponymous city, and Rore and Willaert dominated the Venetian music for much the first half of the sixteenth century. The situation of Jacquet is a curious one, for he shares with Gombert, Willaert, and Manchicourt the distinction of being the subject of single-author motet publications (this happened in 1539, all of the previous motet publications were anthologies of multiple authors). Stylistically, neither the Mediterranean climate nor the Italian preference for light, chordal music have changed his allegiance, and his style is very much in line with his Franco-Flemish compatriots. He wrote exclusively sacred music, and especially in field of masses he was second only to Morales in number, though less versatile and not as uniformly excellent as the great Spaniard. The relative paucity of his imagination can be revealed by a comparison of his five voice Missa Si Bona Suscepimus with Morales’s classic just discussed. There is much repetition of almost the same material across the opening of sections, and a tendency of presenting the material in the motet rather literally. However Jacquet does tend to present a more rigorously imitative texture, and fugal entries are more common than Morales, who prefer largely non-imitative free counterpoint where the subject is only presented in a few voices. On the other hand, Jacquet excels at adaptation of the lighter forms such as chanson and madrigals to the mass, and his imitation masses on De mon triste displasir, and Ancor che non partire are vivid and flexible adaptations which preserve the tunefulness of the chanson and the syllabic declamation of the madrigal.

Further north in the peninsula, Rore is best remembered as one of the finest composers of madrigals, though he left not an insubstantial amount of sacred music behind, and the powerful declamatory style of his madrigals informed the style of his sacred music as well. Rore’s mentor, Willaert, was one of the foremost composers and innovators of his time. With a career spanning well over fifty years, Willaert had mastered all the major genres of the time, and created an elusive but highly personal style that is distinct from the prevailing method of pervasive imitation. He was a pupil of Mouton, and much of his imitation masses were indeed based on motets by or attributed to Mouton. The smooth, graceful lines of his counterpoint also speaks of Mouton’s influence. Yet Willaert polished his style further as he aged and turned it into a far more subtle and abstract art. His greatest works were collected and published in 1559 under the title Musica Nova, which contains, exceptionally for its time, a collection of 25 motets and 27 madrigals40. Willaert has always stood at the vanguard of polyphonic music: in the early 1510s he had participated in the first flowering of the imitation mass; in 1540 he, together with colleagues at Venice, published one of the first instrumental ricercars; earlier in the 1550s he and Jacquet of Mantua had also put out a collection of psalms for two choirs, which became a model for the eventually flowering of double choir technique utilised by his successors at St Mark’s. But it was the 1559 publication that confirmed the profundity of Willaert’s art. We have noted that the style of motet and mass converged as one assimilated the influence of the other, and here in the Musica Nova Willaert had amalgamated the styles of the motet and the madrigal (Figure 15). In both types of works a dense texture pervades with little rest, and the frequent movement in thirds of the bass together with the lack of clear modal function in the voices severely weaken the modal unity of each piece. Imitation is largely abandoned as an organisation tool, and apart from occasional repetitions of tiny motivic gestures across voices, there is little else that holds the parts together. The sacrifice of melodic unity leads to the enhancement in another area: declamation of text. Willaert’s meticulousness in setting the syllables of the words to the notes was one of the primary innovations of the Musica Nova, and his pupil, Zarlino, had used it as a boundary between music new and old. The text setting is largely syllabic throughout and eminently comprehensible, which is in direct contrast to the style of Gombert where initial syllabic settings quickly give way to extended melismas on the penultimate syllable, and the words are frequently obscured by the contour of the melody in the imitation or the general unruliness of the other voices. It’s easy to get lost in the subtlety of Willaert’s music, but with a little attention, the words can always be clearly discerned, even when the voices are out of phase with each other and rarely ever come together. Willaert’s demonstration of his composer’s art is most conspicuous in the large number of canons throughout the collection. Yet this is only apparent on the page, since the canonic voices are buried inside the texture and blend imperceptibly with the free voices, and hidden from listeners. Willaert’s style is a perfect representative for the attitudes of his generation: a preoccupation with subtlety, care, and understatement that clothes the underlying complexity of the music with a smooth surface. In the words of Taruskin41

The result is a music that is carefully and expertly controlled in every dimension, yet one without a hint of flashy tour de force. That is as good a description as any of a “classic” style.

Figure 15: Adrian Willaert, Cantai: or piango, Part 1, (1559). Click for audio.

The End of Perfection

Soon after the death of Emperor Charles V in 1558, the musicians of his generation also died or faded from the music scene. They have invented and perfected the musical style which accompanied his reign and was in turn generously patronised by him, and now they too faded into history with the Emperor. Morales had succumbed to disease in 1553, the “Wolfpack” had died 10 years prior, and the other great names of the day, Crecquillon, Clemens, and Jacquet were all dead by the end of the decade. Willaert passed away in 1562, three years after the publication of his Musica Nova, and Rore followed in 1565. Manchicourt had also died during his tenure as Philip II’s choirmaster in 1564.

The ars perfecta of the mid 1550s was already under assault even as it asserted dominance over the music scene. The rise of the madrigals with its sensitivity (or indeed hypersensitivity) to the libretto at the expense of polyphony posed the greatest threat. Gradually the more dramatic style won out and the invention of monody permanently ossified the old polyphonic style. Isolated holdouts still existed in the periphery into the 17th century, and musician’s skills in weaving a continuous imitative contrapuntal fabric was highly uneven once the practice faded out of general usage. In the late 1590s, a composer like Alonso Lobo could still effortlessly write six part masses in the traditional style. And one can identify his heritage through Victoria, Guerrero and Morales all the way back to Josquin and beyond. While an Italian composer like Ipolitto Baccusi clearly struggled to emulate the density and gravity of Gombert. Even Monteverdi was uneasy when he tried to incorporate the power of the previous generation, and his sole foray into what we call parody or imitation mass demonstrates his unfamiliarity with the idiom. The fumbling of so great a composer as Monteverdi is particularly striking if we take into account that a mere 12 years before the publication of his mass, a Fleming not much older than himself published a mass on another Gombert motet which shows no such awkwardness42.

The intensity of the previous generation’s style had proved inimical to the taste of the coming generation, and there was a subsequent relaxation and simplification of the textures of the previous generation. By this time, their reins passed on to two musicians who were born within a few months of each other: an expat Fleming from Mons and a native of a little village outside Rome. Lassus focused on ever clearer declamation and harmonic oriented writing, while Palestrina’s concern was in the footsteps of Morales, towards a more rigorous treatment of dissonance, and a full but controlled texture more in the vein of Josquin than any of his immediate predecessors. More importantly, the rise of a new generation of madrigal writers native to Italy carried the genre to the heights of expression. The subtle art of Willaert had little influence outside his pupils in Venice, and the major madrigalists of the latter half of the sixteenth century, Wert, Marenzio, Luzzaschi, d’India, and of course, Monteverdi, turned towards stranger and more chromatic harmonies, more disjointed melodies and frequent contrasts of groups of voices to achieve an emotional treatment of text that may be described as mannerist. The music of Josquin and Gombert still held sway as they were continually sung in certain major institutions, and studied in entablatured versions on the lute and organ. However, just like the music of the “Tinctoris Five” had all but disappeared from the conscious of composers active in the 1520s, eventually even the best compositions of even Josquin himself and his followers ceased to be sung. They lay dormant in manuscripts and prints scattered throughout Europe, indifferent to the passing ages and the changing styles.

Ad nos vix tenuis famae perlabitur aura.

There scarcely wafts to us a thin breath of their fame.

Virgil, Aeneid, VII, 646

-

Wegman, Rob C. “The State of the Art.” Renaissance? Perceptions of Continuity and Discontinuity in Europe, c.1300–c.1550. Accessed September 17, 2019. https://www.academia.edu/2079825/The%5FState%5Fof%5Fthe%5FArt. ↩︎

-

Vendrix, Philippe. “Introduction. Defining the Renaissance in Music.” In Music and the Renaissance : Renaissance, Reformation and Counter-Reformation, xiii–xxxiv. A Library of Essays on Renaissance Music. Ashgate, 2011. https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00980777. ↩︎

-

Palisca, Claude V., and Henry L. Lucy G. Moses Professor of Music Claude V. Palisca. Music and Ideas in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. University of Illinois Press, 2006. ↩︎

-

“Introduction: The History of What?” In Music from the Earliest Notations to the Sixteenth Century, Oxford University Press. (New York, USA, n.d.). Retrieved 10 Mar. 2020, from https://www.oxfordwesternmusic.com/view/Volume1/actrade-9780195384819-miscMatter-021008.xml ↩︎

-

John Milsom, ‘Imitatio, Intertextuality and Early Music’ in Citation and Authority in Medieval and Renaissance Musical Culture: Learning from the Learned, ed. Suzannah Clark and Elizabeth Eva Leach (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2005), 141–5 ↩︎

-

The term originates from Sean Gallagher, as stated in Rodin, Jesse. “Correspondence.” Early Music 42, no. 3 (August 1, 2014): 508–508. https://doi.org/10.1093/em/cau066. ↩︎

-

See for example the description in Reese’s monograph on the Renaissance. Reese, Gustave. Music in the Renaissance. Dent, 1959. ↩︎

-

Kirkman, Andrew. “The Invention of the Cyclic Mass.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 54, no. 1 (April 1, 2001): 1–47. https://doi.org/10.1525/jams.2001.54.1.1. ↩︎

-

Wegman, Rob C. “Petrus de Domarto’s ‘Missa Spiritus Almus’ and the Early History of the Four-Voice Mass in the Fifteenth Century.” Early Music History 10 (1991): 235–303. ↩︎

-

Sherr, Richard. “Thoughts on Some of the Masses in Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, MS Cappella Sistina 14 and Its Concordant Sources (or, Things Bonnie Won?T Let Me Publish).” In Uno Gentile et Subtile Ingenio, 319–33. Epitome Musical. Brepols Publishers, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1484/M.EM-EB.3.2700. ↩︎

-

For a fascinating detail on the unique structure of this mass, see Alejandro Planchart’s notes in his new edition of Du Fay’s works, and Wegman’s article on its genesis. Wegman, Rob C. “Miserere Supplicanti Dufay: The Creation and Transmission of Guillaume Dufay’s Missa Ave Regina Celorum.” The Journal of Musicology 13, no. 1 (1995): 18–54. https://doi.org/10.2307/764050. ↩︎

-

Planchart, Alejandro Enrique Planchart. “The Origins and Early History of L’homme Armé.” The Journal of Musicology 20, no. 3 (2003): 305–57. https://doi.org/10.1525/jm.2003.20.3.305. ↩︎

-

For a description, see Taruskin. Though Taruskin’s thesis that Busnoys was the progenitor for the L’homme arme tradition remains controversial. Taruskin, Richard. “Antoine Busnoys and the ‘L’Homme Armé’ Tradition.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 39, no. 2 (1986): 255–93. https://doi.org/10.2307/831531. ↩︎

-

Luko, Alexis. “TINCTORIS ON VARIETAS.” Early Music History 27 (2008): 99–136. <10.1017/S0261127908000296>. ↩︎

-

Bernstein, Lawrence F. “Jean d’Ockeghem.” The Cambridge History of Fifteenth-Century Music, July 2015. https://doi.org/10.1017/CHO9781139057813.011. ↩︎

-

Perkins, Leeman L. “In Memoriam Dragan Plamenac: The L’Homme Arme Masses of Busnoys and Okeghem: A Comparison.” The Journal of Musicology 3, no. 4 (1984): 363–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/763587. ↩︎

-

Godt, Irving. “An Ockeghem Observation: Hidden Canon in the ‘Missa Mi-Mi?’” Tijdschrift van de Vereniging Voor Nederlandse Muziekgeschiedenis 41, no. 2 (1991): 79–85. https://doi.org/10.2307/938805. ↩︎

-

See the liner notes for the Clerks’ Group’s recording of this mass in their complete recording of Ockeghem’s collected works. ↩︎

-

Sherr, Richard. “Thoughts on Ockeghem’s Missa De plus En plus: Anxiety and Proportion in the Late 15th Century.” Early Music 38, no. 3 (2010): 335–46. ↩︎

-

Rob Wegman’s liner notes for the Clerks’ Group’s recording of the Missa Ecce Ancilla Domini. ↩︎

-

Wegman, Rob C. “The Anonymous Mass D’Ung Aultre Amer: A Late Fifteenth-Century Experiment.” The Musical Quarterly 74, no. 4 (1990): 566–94. ↩︎

-

This and most of the following information derive from Wegman’s (magisterial) monograph. Wegman, Rob C. Born for the Muses: The Life and Masses of Jacob Obrecht. Oxford Monographs on Music. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 1996. ↩︎

-

Milsom, John. “Making a Motet: Josquin’sAve Maria … Virgo Serena.” The Cambridge History of Fifteenth-Century Music, July 2015. https://doi.org/10.1017/CHO9781139057813.017. ↩︎

-

Rodin, Jesse. “‘When in Rome…’: What Josquin Learned in the Sistine Chapel.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 61, no. 2 (2008): 307–72. https://doi.org/10.1525/jams.2008.61.2.307. ↩︎

-

Meconi, Honey. Pierre de La Rue and Musical Life at the Habsburg-Burgundian Court. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 2003. ↩︎

-

La Rue wrote 8 five voiced masses and 1 six voiced mass, further two masses expand to 5 voices in their Credo. Meconi, Honey. La Rue [de Platea, de Robore, de Vico, Vander Straeten], Pierre [Perison, Peteren, Petrus, Pierchon, Pieter, Pirson] De. Oxford University Press, 2009. https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000016044. ↩︎

-

Antico, Andrea. Misse Quindecim a diversis optimis et exquisitissimis Auctoribus, 1516. https://opac.rism.info/search?id=993103881&View=rism ↩︎

-

Fitch, Fabrice. “Agricola and the Rhizome: An Aesthetic of the Late Cantus Firmus Mass.” Revue Belge de Musicologie / Belgisch Tijdschrift Voor Muziekwetenschap 59 (2005): 65–92. ↩︎

-

See for example, the grove article. Wegman, Rob C., Fabrice Fitch, and Edward R. Lerner. Agricola [Ackerman], Alexander. Oxford University Press, 2001. https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000052210. ↩︎

-

Fitch, Fabrice. “O Tempora! O Mores!: A New Recording of Obrecht’s ‘Missa Maria Zart.’” Edited by Jacob Obrecht, Tallis Scholars, and Peter Phillips. Early Music 24, no. 3 (1996): 485–95. ↩︎

-

For more information on Attaingnant’s career as music printer, see Bazinet, Geneviève. “SINGING THE KING’S MUSIC: ATTAINGNANT’S MOTET SERIES, ROYAL HEGEMONY AND THE FUNCTION OF THE MOTET IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY FRANCE.” Early Music History 37 (October 2018): 45–89. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261127918000037. ↩︎

-

Steib, Murray. Imitation and Elaboration: The Use of Borrowed Material in Masses from the Late Fifteenth Century. University of Chicago, 1992. ↩︎

-

For a discussion of Josquin’s authorship of the mass, see: Elzinga, Harry. “Josquin’s ‘Missa Quem Dicunt Homines’: A Reexamination.” Tijdschrift van de Vereniging Voor Nederlandse Muziekgeschiedenis 43, no. 2 (1993): 87–104. https://doi.org/10.2307/938720. ↩︎

-

Cumming, Julie E., and Peter Schubert. “The Origins of Pervasive Imitation.” The Cambridge History of Fifteenth-Century Music, July 2015. https://doi.org/10.1017/CHO9781139057813.018. ↩︎

-

The best prose introduction to Gombert’s works is Rob Wegman’s booklet notes for The Sound and the Fury’s recording of his Missa Quam Pulchra Es, which forms the basis for this paragraph. ↩︎

-

Jas, Eric. Beyond Contemporary Fame: Reassessing the Art of Clemens Non Papa and Thomas Crecquillon. Turnhout: Brepols, 2005. ↩︎

-

Elders, Willem, Kristine Forney, and Alejandro Enrique Planchart. Clemens Non Papa, Jacobus. Oxford University Press, 2001. https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000005930. ↩︎

-

Stevenson, Robert Murrell, and Robert Stevenson. Spanish Cathedral Music in the Golden Age. University of California Press, 1961. ↩︎

-

An edition of his magnificats was brought out by Scotto that year. ↩︎

-

Carapetyan, Armen. “The ‘Musica Nova’ of Adriano Willaert.” Journal of Renaissance and Baroque Music 1, no. 3 (1946): 200–221. ↩︎

-

Richard Taruskin. “Chapter 15 A Perfected Art.” In Music from the Earliest Notations to the Sixteenth Century, Oxford University Press. (New York, USA, n.d.). Retrieved 1 Jul. 2019, from https://www.oxfordwesternmusic.com/view/Volume1/actrade-9780195384819-div1-015007.xml ↩︎

-

Philippe Rogier’s Missa Ego sum qui sum, on a six part motet also by Gombert ↩︎