Canonic principles of La Rue's Missa O Salutaris Hostia

Oct 16 2018Introduction

Although rarely recognised as such, Pierre de La Rue’s Missa O salutaris Hostias is one of the most remarkable contrapuntal achievements of the Franco-Flemish Renaissance alongside Ockeghem’s Missa Prolationum and Forestier’s Missa L’homme arme. Like the other two, it explores systematically one single aspect of canon, namely that of 4-ex-1 canon. This places the most significant constraint of the three on it since unlike Forestier’s mass, there are no free voices, and unlike Ockeghem’s mass, all four voices derives from a single melody. The restrictions on generating a harmonic sensible and musically intelligible piece from a single melody line must have been enormous, and it’s therefore surprising that not only has La Rue managed to create a 30 minute long piece without monotony kicking in (unlike Forestier), but that the music flows with astonishing grace that belies its canonic conception (much like Ockghem).

Nevertheless there are formidable problems to be resolved in realising the work for the modern audience. Since the work survives in its two earliest sources in a canonic notation, where the other three voices are to be realised by the singer1, 2. The construction of the canon is identical throughout the mass: there are two canonic duos, in each duo the comes enters at the lower fifth. This duo is then duplicated at the upper or lower octave by the other two voices. The interval of the canonic imitation immediately raises the question of whether the canon is exact or diatonic. That is to say, whether the comes would duplicate the exact intervals of the dux by singing with an extra flat sign (Eb in this case), and repeat the cadential inflection of the dux as well, or whether the comes would sing E natural and hence sing with the same number of signature flats as the dux.

Fortunately, significant ground has be tread in this direction by Peter Urquhart thirty years ago who dealt extensively with this problem in the works of Josquin3. This article is therefore heavily indebted to the terminology and methodology of Professor Urquhart’s works. However, he has noted that the scope of the repertory meant that he was not able to conduct more than a cursory overview of the works of Josquin’s most significant contemporary who also wrote many canons. And his comment on the O Salutaris Hostias mass is limited to a single sentence4

The Missa O Salutaris is a 4 ex 1 composition of surprising grace. No transcription exists to my knowledge; my initial investigation of the piece indicates that it contains diatonic canons.

The mass has now been published in a modern edition as part of the CMM project5, and a transcription can be found on the Josquin research project website6. More significant to audiences would be the release of a recording by The Sound and the Fury back in 2010, which for the first time allowed us to hear the “surprising grace” which Urquhart has seen by perusing the score some thirty years ago. Nonetheless, the question remains of the nature of the canon, and by extension, the inflection of accidentals, which were not entirely consistent nor satisfactory in the recording.

Theoretical background

The Hand and Musica Ficta

Non-Transposing Pitches

Central to Urquhart’s dissertation is the concept of the “non-transposing pitch”, which are the pair of pitches which inflection is uncertain, he writes7:

NTP is the pair of pitches in the dux and comes of a canon at the 4th or 5th, between which a perfect interval does not exist within the assumed background diatonic collection.

In our case, where the written out voice, always the dux and leading by the upper fifth, is always presented with a single flat signature sign, the assumed background would be the one-flat signature. The non-transposing pitch is B in the dux, and E in the comes, as summarised in table 1 below.

| Signature | Canon interval | Pitch in dux | Pitch in comes |

|---|---|---|---|

| One-flat | Lower fifth | B | E |

To figure out whether a diatonic or exact canon is intended from the composer from purely internal evidence requires us to catalogue and investigate every single occurence of these Non Transposing pitches in the piece.

Singer inflection

When faced with a canonic work, Urquhart suggestes that there are two ways of approaching the problem8: Either singers were aware of the context and adjusted their inflection accordingly, and the inflection of the canon is not fixed. Or the composer had clearly in mind whether the canon would be diatonic or exact and communicated his intentions through consistency and unambiguous signs throughout. If the former were the case then how the NTPs were inflected would be largely haphazard, with the inflection of one voice not giving any hints in the subsequent inflection of the other. On the other hand if composers decided a priori on the type of canon he wishes to compose, there would be a consistent and clear preference for maintaining the same canonic relationship throughout, whether diatonic or exact, and singers would have a much easier job singing through the lines.

The Music

Canonic structure

Similar to its sibling mass Missa Ave sanctissima maria, there are no free voices in the entire piece, and every movement is constructed out of canon. Also similar to La Rue’s other canonic masses, the intervallic content of the canon Missa O salutaris hostia follow the same rigid scheme throughout, the canon is always at the lower fifth, at a distance of two breves for C mensurations, and one breve for O mensurations (see table 2, the only two duets in the mass vary the temporal distance somewhat, but retain the interval of the canon). The voices always enter in pairs, and the second pair reproduces the pitches of the first pair either up or down an octave. In this light, it is perhaps more instructive to treat the voice as pairs, not the least because a significant portion of the mass consists of alternating duets. Stretches of sustained four voice tutti are only found at the end of the Et in terra (bars 38-77), Patrem (bars 54-121) and Osanna (bars 72-106).

| Movement | Mensuration | Voice distance | Pair distance | Pair direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kyrie I | C2 | 2 | 10 | down |

| Christe | C2 | 2 | 8 | up |

| Kyrie II | Cut-O | 1 | 4 | down |

| Et in terra | C2 | 2 | 13 | down |

| Qui toolis | C2 | 2 | 8 | up |

| Patrem | C2 | 2 | 13(6) | down |

| Et resurrexit | C2 | 2 | 13 | up |

| Sanctus | O | 1 | 6 | down |

| Pleni | C2 | 1.5 | - | - (low) |

| Osanna | C2 | 2 | 6 | down |

| Benedictus | C2 | 1 | - | - (high) |

| Agnus I | O | 1 | 5 | up |

| Agnus II | C2 | 2 | 8 | down |

| Agnus III | C3 | 2 | 6 | up |

This disposition the voice in pairs necessarily means that frequently the same duet is heard twice, just at a different pitch level. The monotony that results would be against good taste for music of earlier generations, however Josquin and friends established paired duets as a normal part of the musical style by the first two decades of the 16th century, and La Rue must have considered the ability of the piece to “blend in” with the normal repertory and disguise its rigid canonic principles. Composing a an entire piece out of a single notated voice which is over 750 breves (and lasting nearly 30 minutes in performance) must have presented an extraordinary challenge, and in my knowledge nobody have attempted such a feat before or since. La Rue’s choice may have been to render the challenge more tractable while not making the soundworld too awkward. Under this light, it seems fair to date the piece to the 16th century, possibly towards the end of La Rue’s life.

The evidence

A tabulated result of all the NTP present in the piece is presented as Appendix A below. A few immediate things for comment:

The canon in the Kyrie operates perfectly as either an exact canon or a diatonic canon until the point where it breaks down dramatically at the end of the second Kyrie with a irreconcilable false relation (Figure 1). Exact canon breaks down here in a completely unambiguous manner, since the comes has to sing B-mi to maintain perfect octave with the tenor. Closer inspection also reveals on watertight the inflection is implied: since the dux cannot sing B-mi in bar 70, because he needs to form a perfect octave with the bass; the tenor cannot sing E-fa in bar 71, because that would form a conspicuous melodic tritone with his A in bar 70; the tenor cannot sing A-fa in bar 70, because he needs to maintain a perfect octave with the bass A in bar 70; the bass cannot sing A-fa in bar 70, because that would form a conspicuous melodic tritone with his D in bar 71… In short, anything attempt to force exact canon at this stage would cause a “secret chromatic art” style spiral into the abyss.

Figure 1: La Rue, Missa O salutaris hostia, Kyrie II, bar 70-71. The relevant NTPS are in red, while the notes which impose harmonic constraints on the NTPs are in blue.

The same pitches also occur in the lower duet, and the inflection is also different, this time because of a harmonic fifth between the bass and alto (Figure 2).

Figure 2: La Rue, Missa O salutaris hostia, Kyrie II, bar 74-75. The harmonic NTPS are in red, while the notes which impose harmonic constraints on the NTPs are in blue.

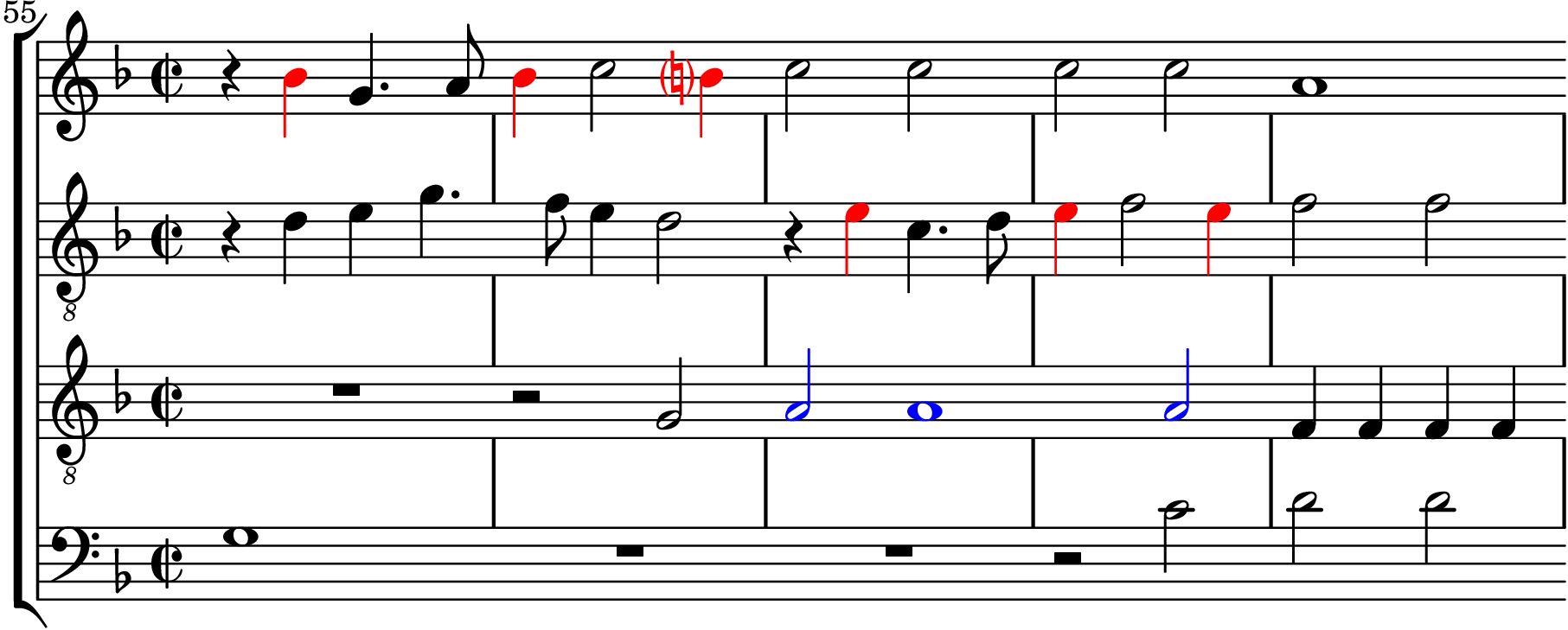

Similarly in the Gloria, harmonic restraints also force dux and comes to inflect differently, where (Figure 3).

Figure 3: La Rue, Missa O salutaris hostia, Et in terra, bar 55-59. The harmonic NTPS are in red, while the notes which impose harmonic constraints on the NTPs are in blue.

The other cases where exact canon breaks down also happen quite a long way into the movement, and is not discernible by eye from reading the canonic notation, unless one keeps track of where all four voices are. From this point of view, it’s impossible, as a singer, to foresee this type of dissonance occuring, and therefore places serious doubts on the feasibility of singing this piece as an exact canon.

-

Liber Quidecim Missarum, Antico, Rome 1516 ↩︎

-

Urquhart, Peter. Canon, partial signatures and “musica ficta” in works by Josquin des Prez and his contemporaries, PhD Dissertation, Harvard University 1988 ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

-

La Rue, Pierre de. Opera Omnia volume V, edited by Nigel St. John Davison, J. Evan Kreider, and T. Herman Keahey. 1996 ↩︎