Cantus lenis? Some mistakes in the modern reception of the Nightingale motet

Aug 26 2018Or, is anyone really listening?

Verdelot’s Mass

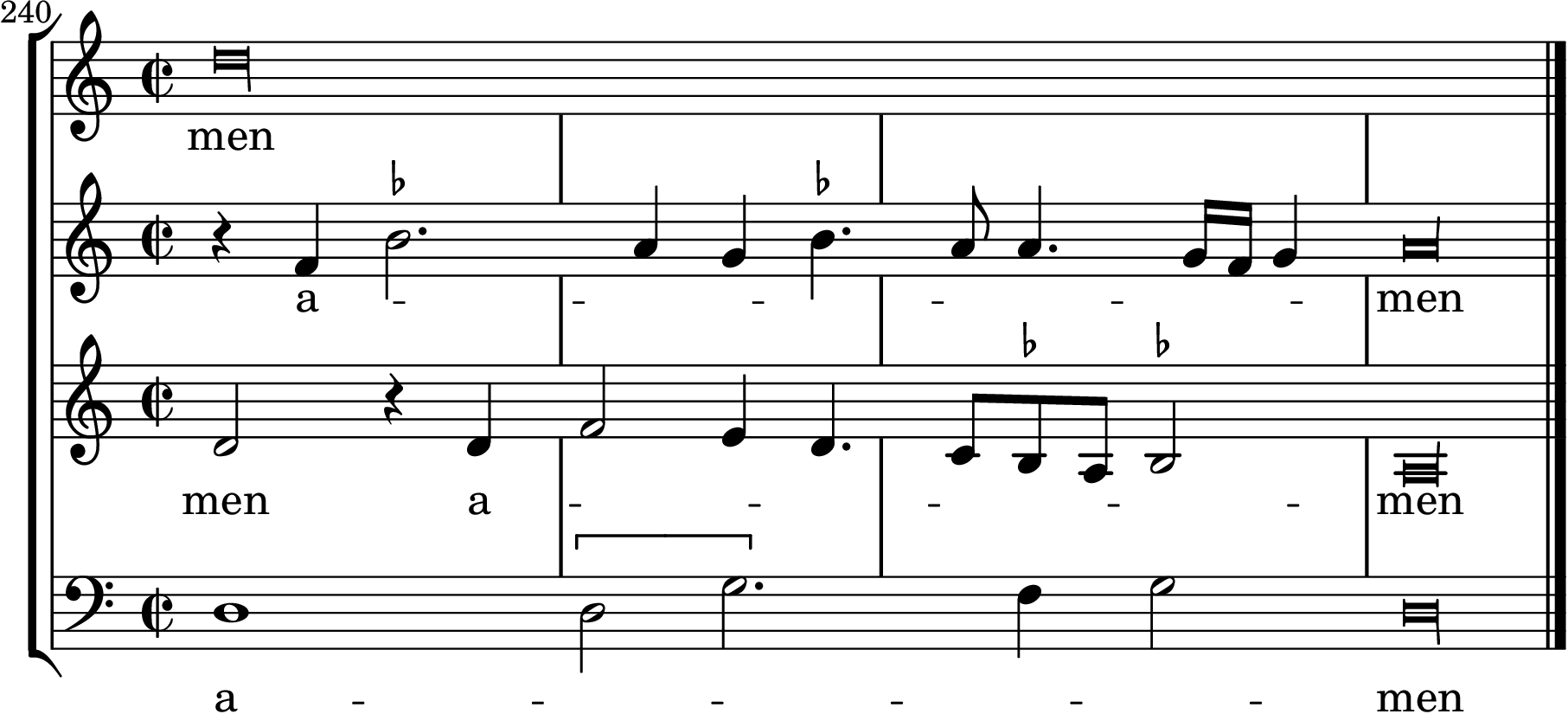

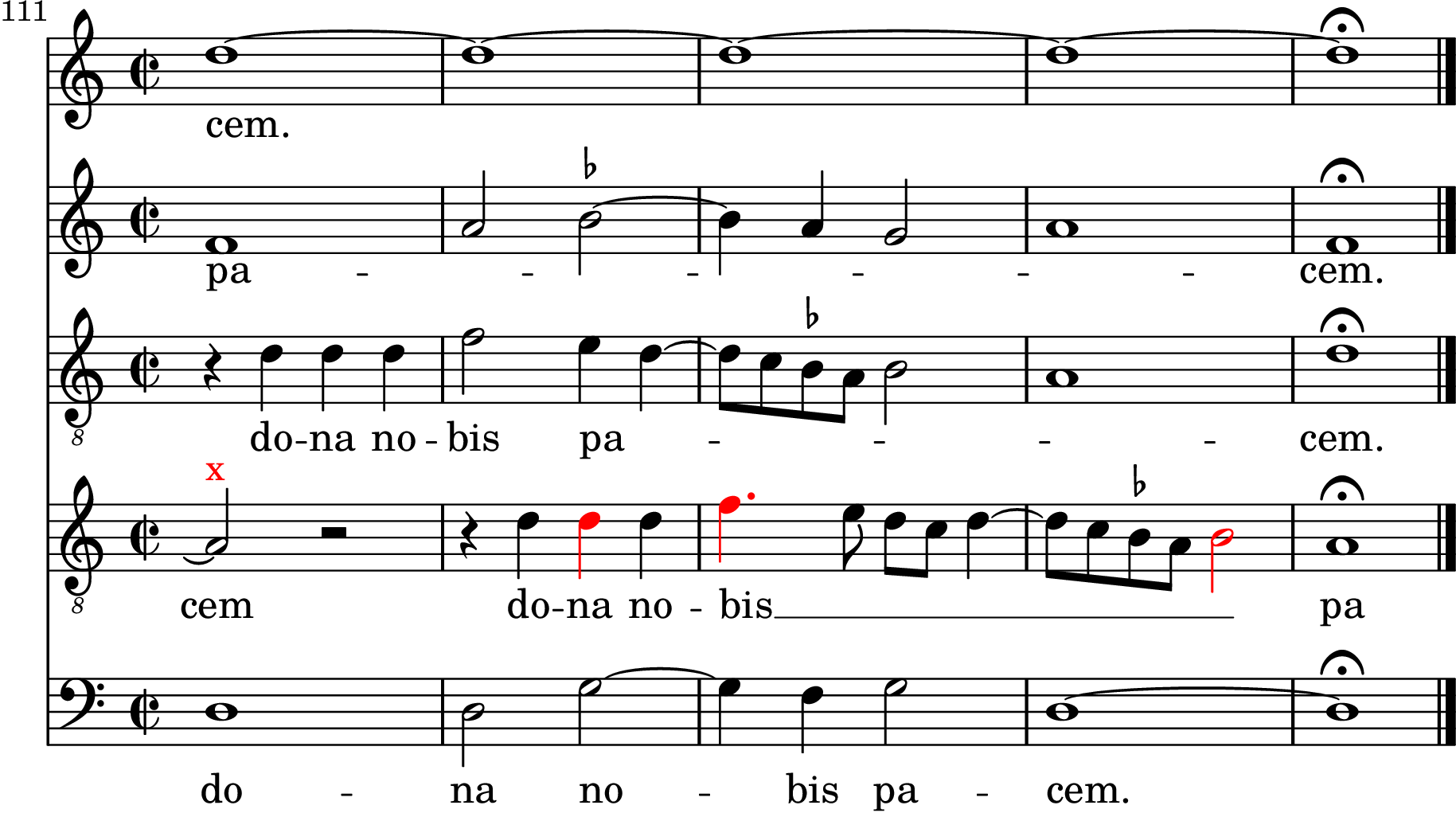

While listening to Verdelot’s Philomena mass1, I was struck by a certain detail which remained with me long after the music has ended. The ending of the Credo (see Figure 1, which reproduces the Verdelot Opera Omnia2) contains a plagal cadential extension which is exceedingly elegant. These extensions are commonplace in the motet and masses of the 16th century since they add weight to the authentic cadence and provide a sense of closure to a long work that the usual short cadential gestures of the period were not able to supply. Usually, at least one voice holds the finalis of the mode, in this case the soprano D, while the other voices circle the consonant scale degrees under it. Verdelot’s altus, which leaps between the 3rd and flattened 6th degree of the mode, is entirely typical, as is the G-F-G-D (or 4-3-4-1 in terms of scale degree) motion in the bass. What makes this passage extraordinary is the insistent leap to B-flat in the altus and the subsequent heartrending 7-6 suspension leading to a stark bare 5th in the final chord. Delitiae Musicae’s sensitive performance, with a tastefully applied ritenuto, adds greatly to the poignancy of the moment.

Figure 1: Plagal extension at the end of the Credo of Verdelot’s Missa Philomena, from Verdelot Opera Omnia, Vol 1. pp 17. Click for audio.

Plagal cadential extensions also appear in many other section of Verdelot’s mass, but none as elaborate or lengthy as in the end of the Credo. Since the Credo is by far the wordiest and lengthiest section of the mass, it naturally requires the proportionally most substantial coda. This ending is actually taken almost note by note from Richafort’s original (see Figure 2, which reproduces the Richafort Opera Omnia3). Its sole appearance at the end of Verdelot’s Credo reflects his judicious choice in selecting the most approprioate sections of Richafort’s motet for sections of his mass. The making of a great imitation mass depends not as much on what one pilfers from the original but rather where one places the pilferings inside one’s own work. All great writers of imitation masses restrict themselves to only use certain sections from the original in a select few passages in their imitation. In this sense withholding the borrowed passages at certain sections is as much a conscious decision as the choice to employ borrowed passages. Verdelot’s restraint in quoting Richafort’s ending demonstrates his deep understanding of creating an effective imitation mass.

Since the recording by Delitiae Musicae of Verdelot’s mass also included Richafort’s motet (a practice that has become lamentably rarer as of late), I turned to it for comparison. I was expecting something more or less resembling Figure 2, so imagine my surprise when I heard something quite different4.

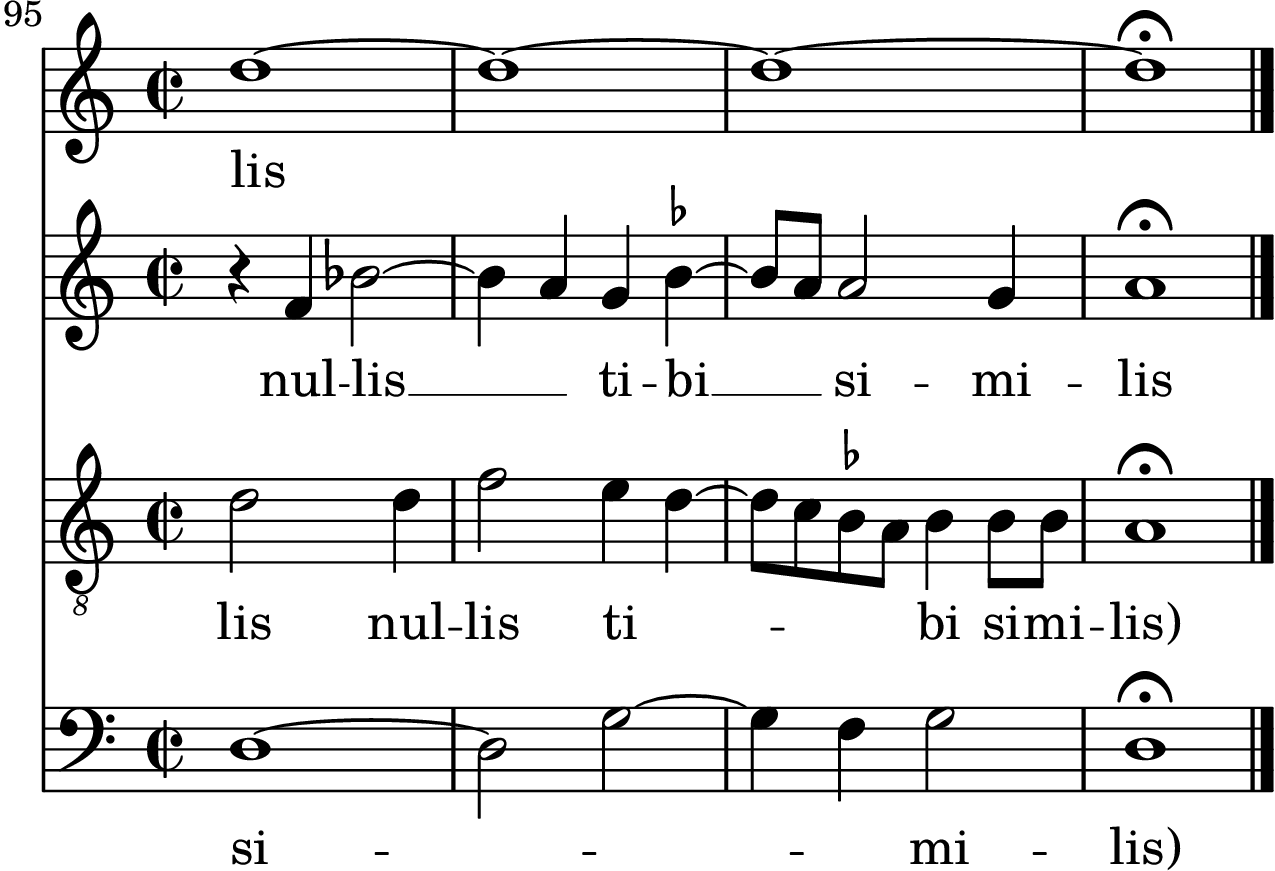

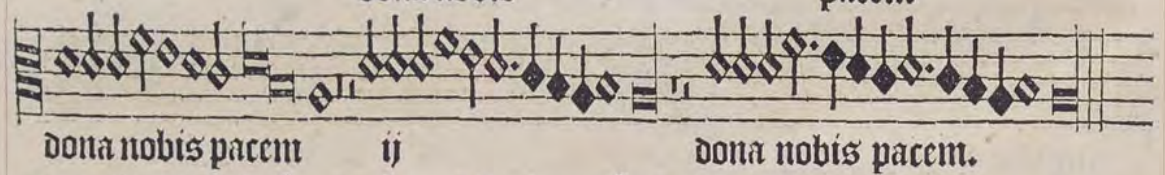

Figure 2: The ending of Richafort’s Philomena Praevia, from Richafort Opera Omnia vol. 5, pp 134. Click for audio.

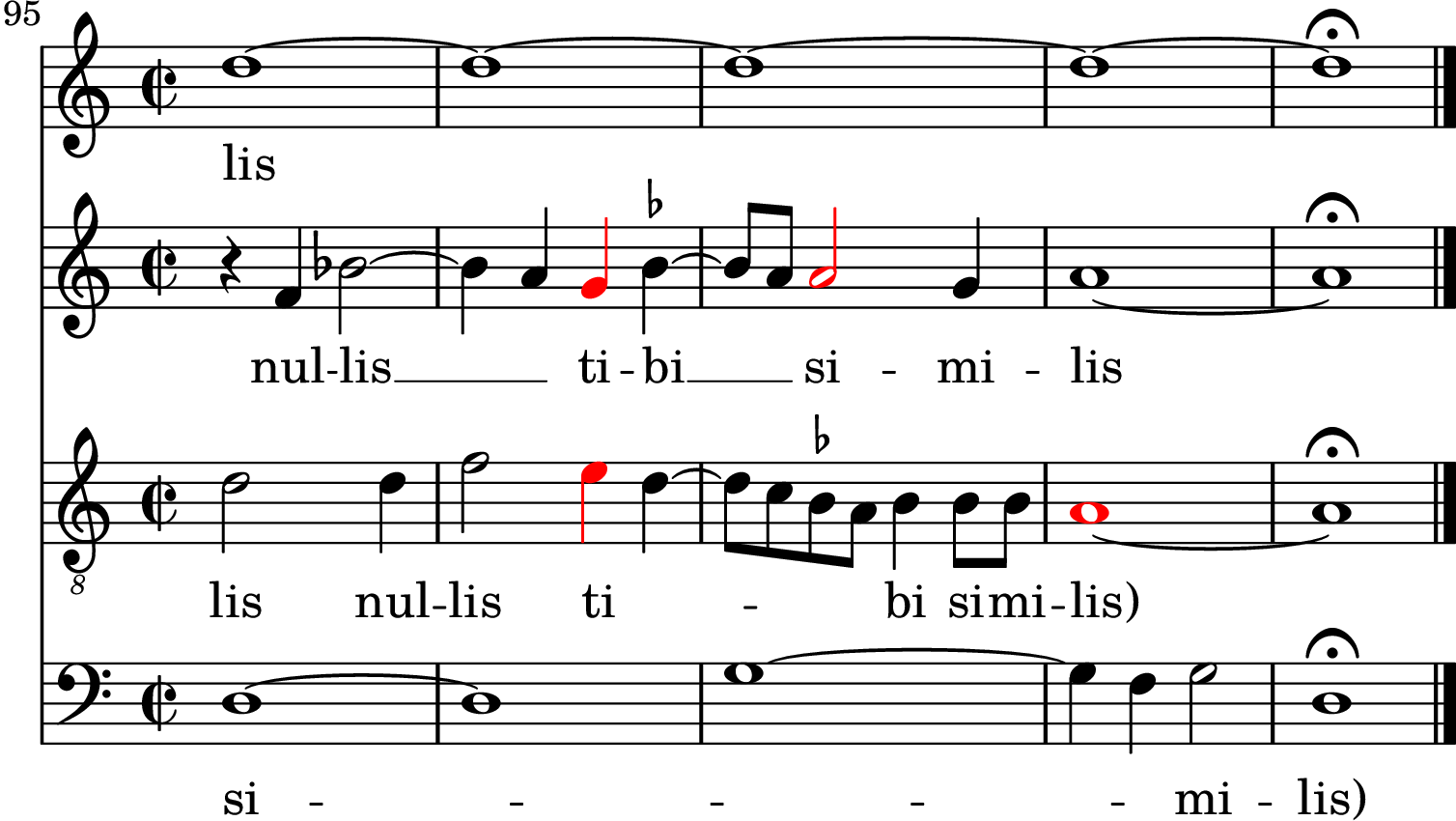

For some reason, the bass in the recording has decided to sing Figure 3. You can hear it here. The entry of the Bass to the G was delayed by a minim and the g was held for a semibreve instead of a minim. Why the bass decided to contradict the modern edition is not clear, for it clearly makes no contrapuntal sense. This change removes the harmonic support in the latter part of bar 96, changes the suspension in bar 97 into something extremely awkward, and makes nonsense of the 4-3-4-1 cadential extension in the bass. The notes in red in Figure 3 show the notes which have become dissonant against the new bass.

Figure 3: The ending of Richafort’s Philomena praevia as sung by Delitiae Musicae. Click for audio.

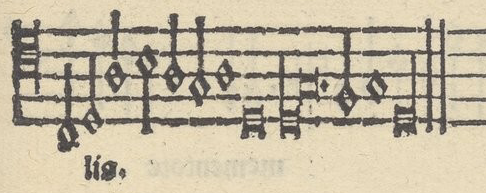

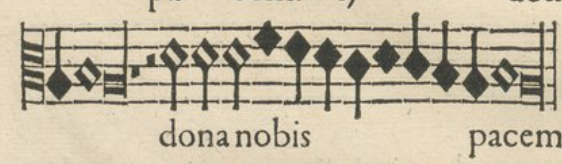

After inspecting one of the early sources, I’m certain that the singers were acting on their own accord. In the Attaignant print of 1528 (Figure 4), the bass is given correctly, as is the modern edition reproduced above5. One can only speculate on why the director of Delitiae Musicae, Marco Longini, decided to carry out this change. Perhaps he wanted to add a bit of improvisation by delaying the ending of the bass, but the foundation of Renaissance improvisations is the embellishment of the underlying simple note-by-note counterpoint by adding notes of dinimished values to create florid counterpoint. Changing the underlying structure of the simple counterpoint is not really inside the purview of improvisation, especially if it leads to untolerable dissonances, as the singers themselves would have surely noticed.

Figure 4: The ending of the bass of Philomena from Attaignant’s 1528 motet print.

Sermisy’s Mass

Richafort’s motet proved quite popular with contemporaries, for Claudin de Sermisy also wrote a mass based on it. It is always enlightening to compare and contrast the results of different composers dealing with the same material, and here Sermisy’s treatment of Richafort’s ending is quite different from Verdelot’s. Sermisy produced a contracted version of the plagal extension at the end of the Kyrie, and, to my disappointment, did not use it in the ending of Credo.

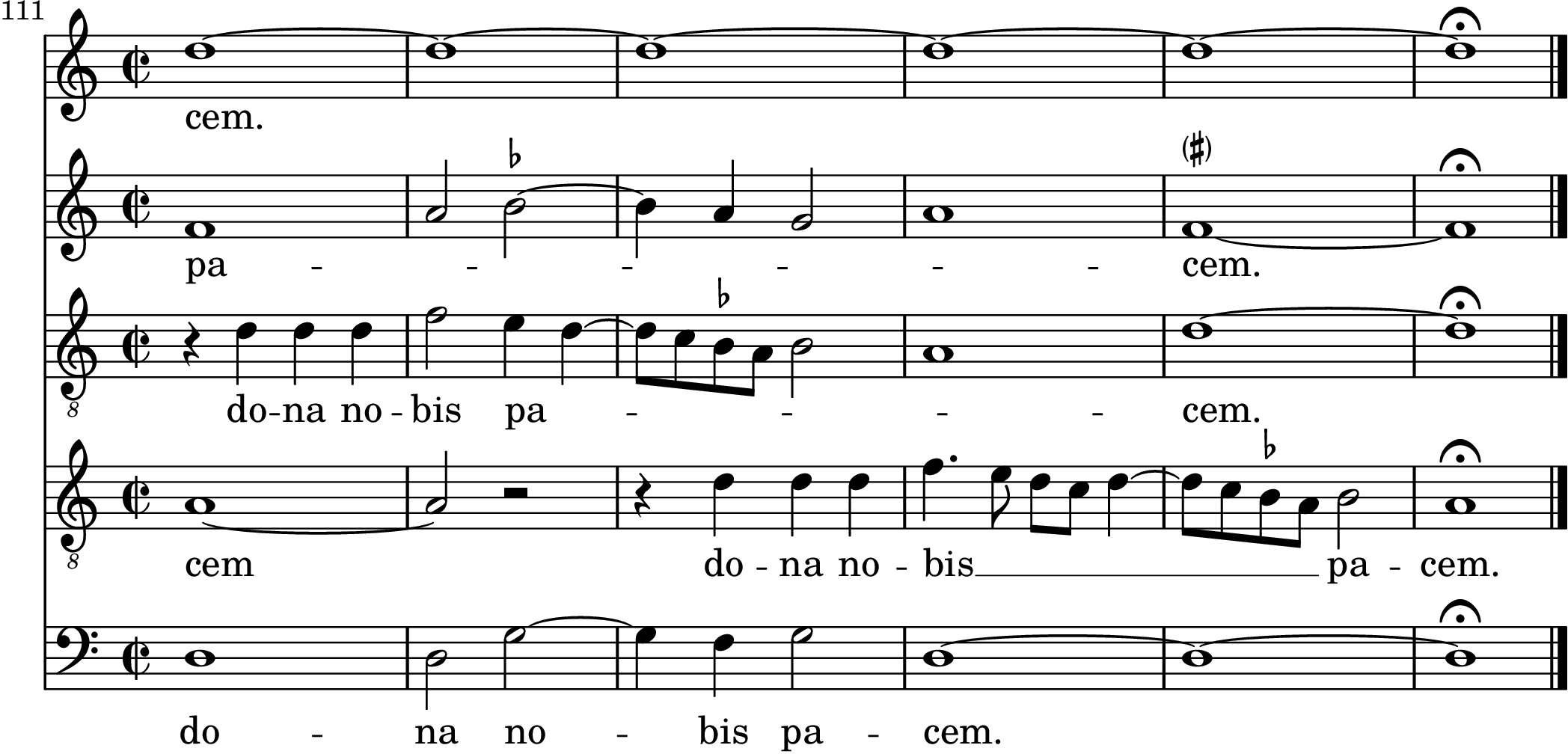

However the full ending does appear in Sermisy’s final Agnus Dei, with the added bonus that this is a section with an additional voice which enriches the texture considerably. It is here that I observed something which is more surprising than anything I’ve come across so far. To begin with, the Sermisy complete edition gives the ending as Figure 5.

Figure 5: The ending of Sermisy’s Missa Philomena as printed in the Sermisy complete edition. Click for audio.

Although the voices have been shuffled around a bit, we can still recognise Richafort’s original in Sermisy’s ending, particularly the bass and superius which remain the same. Sermisy simplified the qltus line by only allow it ascend once to the B-flat and removing the suspension in bar 113. However the music in the original tenor is given to the quintus (3rd voice down), and the tenor imitates the qunitus at the distance of 1 bar. This doesn’t quite work out, and it looks as if Sermisy has botched the effort. The tenor line seems to create some awkward dissonances (highlighted in red) with the surrounding voices. Particularly grinding is the minim B-flat in bar 114 which sounds a minor second against the altus and quintus. What makes this dissonance even more egregious is the fact that it isn’t resolved at all, the two other voices simply leap away from the dissonance as if nothing has happened.

Such a dissonance would certainly be outside the realm of acceptability for early 16th century polyphony, but a little more digging reveals why. Sermisy’s mass is found, among the exmplar in the Leiden Choirbooks, in two contemporary prints: Attaignant’s in 15326, Figure 6; and du Chemin’s in 15687, Figure 7. A cursory look at the ending of the tenor in the two sources reveal what is the case: the tenor A in bar 111 (marked with a red x in Figure 5) which is a semibreve in the modern edition, should really be a full breve. Since the note in both prints is shown to be a long, after reducing values by half for the modern edition the note is brought down one value to a breve. This means that the tenor actually enters one bar too early.

Figure 6: The tenor of Sermisy’s Missa Philomena in the 1532 Attaignant print.

Figure 7: The tenor of Sermisy’s Missa Philomena in the 1568 du Chemin print.

Once we correct this single mistake, then everything else falls into place, as Figure 8 demonstrates. The tenor A cuts out exactly in bar 112 when the bass moves up to G, avoiding a possible dissonance. And moving the subsequent tenor line back one full bar eliminates all the awkward dissonances in Figure 5.

Figure 8: The corrected ending of Sermisy’s Missa Philomena. Click for audio.

The fact that such a mistake escaped the notice of the Sermisy Opera Omnia editors is regrettable, especially since the sources are unambiguous in this regard8. But surely when the Egidius Kwartet and Choir9 performed it, the strange dissonance at the spot would them give them cause to question the accuracy of the edition. Particularly when the version of Sermisy’s mass found in the very Choirbooks they took their repertory from has the correct tenor line (Figure 9).

Figure 9: The tenor of Sermisy’s Missa Philomena in the Leiden Choirbook F.

Alas, this turned out not to be the case, as they duplicate faithfully the error in the modern edition here. One would heave a heavy sigh at this point and wonder if any of the singer had learnt anything over their monumental journey through the musical treasures in the six choirbooks.

But not to worry, surely a review of the recording in a leading classical music magazine magazine by a professionally trained musicologist specialising in Renaissance music would pick out the obvious error10. Professor Fabrice Fitch provides some valid criticism of the performance in his review, part of which I share, particularly the bit about their soprano’s struggle to sing the notes as written under the high clefs. At the intended performance pitch a fifth lower, like in Delitiae Musicae’s performance, the range would suit the singers much better. However Professor Fitch does not mention the obvious mistake in the final Agnus of Sermisy’s mass. It is disappointing to see a seasoned musicologist like Fabrice Fitch missing this glaring error.

Conclusion

In the end this has proved to be a frustrating affair for me as these two performances (of works which may never be recorded again) are now marred by something as basic as the singing of wrong notes. It is depressing to return to Taruskin’s review of a recording of Monterverdi Madrigal11 to see that singer’s literalism when faced with modern editions have not changed in 30 years. Not only are his criticism of the lack of transposition to suit the singer better familiar, but his recounting the way they duly repeat mistakes as relevant as ever.

… every mistake in the edition is right there on the record! The misinterpretation of the mensural relationships in Bevea Fillide mia, the wrong accidentals prescribed there and elsewhere, and even the obvious typos (e.g., p. 64, B-flat for C in the bass, thirteen bars from the end of Mentre io mimvo fiso; p. 91, A for G in the alto, ten bars from the end of Questo specchio ti dono] are all dutifully reproduced. Anyone who has studied elementary counterpoint will immediately know how to correct these mistakes; anyone listening with half an ear will at least know there are mistakes to be corrected. Not our “virtuosi of Cologne,” though, who have been thoroughly trained only to look, not to listen, and who may have picked up from someone’s history book that Monteverdi was a daring harmonist. One can blame old Malipiero for the mensural misinterpretations, perhaps, but no edition will save such robot-minded performers from their play-it-as-written ways.

The question that need to be raised in the end is rather disappointing: is anyone really listening? Or perhaps it is rare for one to simultaneously engage with both the physical beauty of the human voice in concord and the intellectual construct of the music. Nevertheless the music of Richafort, Verdelot and Sermisy, unlike the eponymous nightingale, are too good to be listened to with just one’s ear12.

-

Longini, Marco; Delitiae Musicae, Verdelot: Missa Philomena Praevia, Stradivarius STR33405SD, 1996. A recording of the music can be found here. ↩︎

-

Bragand, Anne-Maria; Verdelot Opera Omnia Vol. 1 CMM 28, American Institute of Musicology, 1966 ↩︎

-

Allaire, Gaston; Cazeaux, Isabelle; Richafort Opera Omnia Vol. 5 CMM 52, American Institute of Musicology, 1977 ↩︎

-

Bar 95 in the tenor seems to be missing a beat here, but this may be due to the poor resolution of the scan available on IMSLP. According to Attaingnant’s print, there should be a crotchet rest between the minim and crotchet Ds in the modern edition. ↩︎

-

Attaignant, Pierre; Motetz nouvellement composez Imprimeez, 1528, Paris ↩︎

-

Attaignant, Pierre; Primus liber viginti missarum, 1532, Paris ↩︎

-

Chemin, Nicolas du; Missa cum quatuor vocibus Ad imitationem Moduli Philomena, 1568, Paris ↩︎

-

In fact, my correction brings another interesting dissonance into view, if the altus were to sing a picardy third and raise the held F, and the tenor were to sing B-flats like in the motet, then a diminished third results between the two voices which is a very strange interval for Renaissance music indeed. However justifying this would require a much longer discourse than space available at the footnotes here so it is suffice to say that the inversion of this interval (the augmented sixth) has been found in authors such as Clemens non Papa and Thomas Morley and it seems to be a natural way of pushing the boundaries of the dissonance treatment of the time. ↩︎

-

Groot, Peter De; Egidius Kwartet & College; The Leiden Choirbooks, Volume VI., Et Cetera KTC 1415. A recording of the music can be found here. ↩︎

-

Fitch, Fabrice; Review: The Leiden Choirbooks Volume 6, Gramophone, retrieved from here. ↩︎

-

Taruskin, Richard; The Price of Literacy, or Why We Need Musicology, in Text and Act: Essays on Music and Performance, 1995, Oxford University Press ↩︎

-

A confession: although your humble author has had these recordings for quite some years, the contents of this post were only discovered recently. Nevertheless one would hope that professional singers, editors and reviewers would pay rather more attention to their livelihood than a complete amateur and outsider. ↩︎