Review: Guillaume Du Fay - Missa Se La Face Ay Pale

Mar 20 2017Recordings

| Conductor | Group | Vocal forces | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Andrew Kirkman | The Binchois Consort | 4 voices, falsettist superius | 34:30 |

| Giuseppe Maletto | Cantica Symphonica | 7 voices, female superius, instruments | 38:27 |

| Antoine Guerber | Diabolus in Musica | 8 voices, falsettist superius | 38:29 |

| Jesse Rodin | Cut Circle | 8 voices, female superius | 28:41 |

| - | The Hilliard Ensemble | 4 voices, falsettist superius | 32:02 |

Introduction

Du Fay's Se La Face Ay Pale mass was the first mass he composed after absorbing the influence of the English Caput mass, and the first of four late cantus firmus masses that he left to us1. It is by far his most popular mass, judging by the number of modern recordings2, and it seems to have carried a special significance for Du Fay and his patrons in his time as well. Together with Ockeghem's Missa Caput and Domarto's Missa Spiritus Almus, it is one of the three most well known masses circulating on the continent in the early 1450s3, and the only one which was based on a secular cantus firmus from a polyphonic composition. Originally thought to be a mass composed for the wedding of a scion of the House of Savoy, like the ballade it was based on, Anne Walters Robertson has provided a convincing argument which associates it instead with the purchase of the Shroud of Turin by the Duke of Savoy4. Its remarkable clarity of structure and lucidity of voice leading exudes a confidence. It is as Andrew Kirkman states in the liner notes to his recording, that it is as if Du Fay has been writing this kind of music for all his life. Contemporary reception of this mass however is much less enthusiastic than the state of its modern discography would have us presume as Richard Sherr has noted5. Nonetheless, its sunny disposition, the comprehensibility of its musical syntax, its lucid structure and the modal clarity ensured its popularity as a modern crowd-pleaser.

Structure and style

Organisation

The most obvious organisation principle is the presentation of the pre-existing melody, or cantus firmus, the disposition of which must have been determined in advance of the other voices, judging by the meticulousness of design and the faithfulness to the original. Here the eponymous tune comes from the tenor of a wedding ballade composed by Du Fay some 20 years earlier. Like his contemporaries, Du Fay did not want to alter the notational appearance of the tenor, and it appears visually unchanged in all five sections of the mass. The only change from the original is the insertion of additional rests, and an accompanying canon instructs the singers to augment the part with respect to the free outer voices in most sections. The tune is sung once through in the Kyrie, Sanctus and Agnus, while it is sung three times through at increasing speeds in the wordier sections of Gloria and Credo middle sections. This forms the scaffolding of the piece.

Surrounding this skeletal layout, Du Fay furnishes the tenor with counterpoint from three surrounding voices, one occupying the same range, one with range higher by about a fifth, and one with range lower than a fifth. This is the same vocal layout as the anonymous Caput mass, and would become more or less standard for the rest of the century6. In the Kyrie, Sanctus and Agnus, fully scored subsections alternate with trios during which the tenor is silent, while all movements are fully scored in the Gloria and Credo. However, those middle sections also follow a common structure, with each subsection statement of the tenor melody preceded by a fast-moving duet, while the sections where the tenor sounds contains much slower moving harmonies. This alteration between duets and fully scored passages act as the large scale articulation of the piece, and help to accentuate the presence or absence of the cantus firmus, hence highlighting its structural functions. The simple elegance and symmetry in these long range structures, reinforced by textual contrasts, is one of the main reasons of its comprehensibility to the modern audience.

The structure is emphasised in the list below:

| Division | Section | Tenor | Melody | Augmentation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kyrie | Kyrie I | Yes | A | 2x |

| Christe | No | - | - | |

| Kyrie II | Yes | B | 2x | |

| Gloria | Et in terra | Yes | A+B | 3x |

| Qui tollis | Yes | A+B | 2x | |

| Cum Sancto | Yes | A+B | 1x | |

| Credo | Patrem | Yes | A+B | 3x |

| Et iterum | Yes | A+B | 2x | |

| Confiteor | Yes | A+B | 1x | |

| Sanctus | Sanctus | Yes | A' | 2x |

| Pleni | No | - | - | |

| Osanna I | Yes | A'' | 2x | |

| Benedictus | No | - | - | |

| Osanna II | Yes | B | 2x | |

| Agnus | Agnus I | Yes | A | 2x |

| Agnus II | No | - | - | |

| Agnus III | Yes | B | 2x |

Here we can see the striking corespondence in design, and the separation into two clear groups. With the Kyrie, Sanctus and Agnus alternating fully scored with trios, while the Gloria and Credo forgo trios in favour of a accelerating tenor in three fully scored sections7.

Phrasing

Du Fay's phrases are short, rhythmically active, and more often than not end with a conclusive cadence. In the fully scored sections, the top voice is the most florid part, filled with playful syncopations against the prevailing beat duly supplied by the altus and bassus. They range from two to eight breves in length, though the average length is somewhere around 4 breves. Imitation is rare, and in this sense the parts are largely independent from each other.

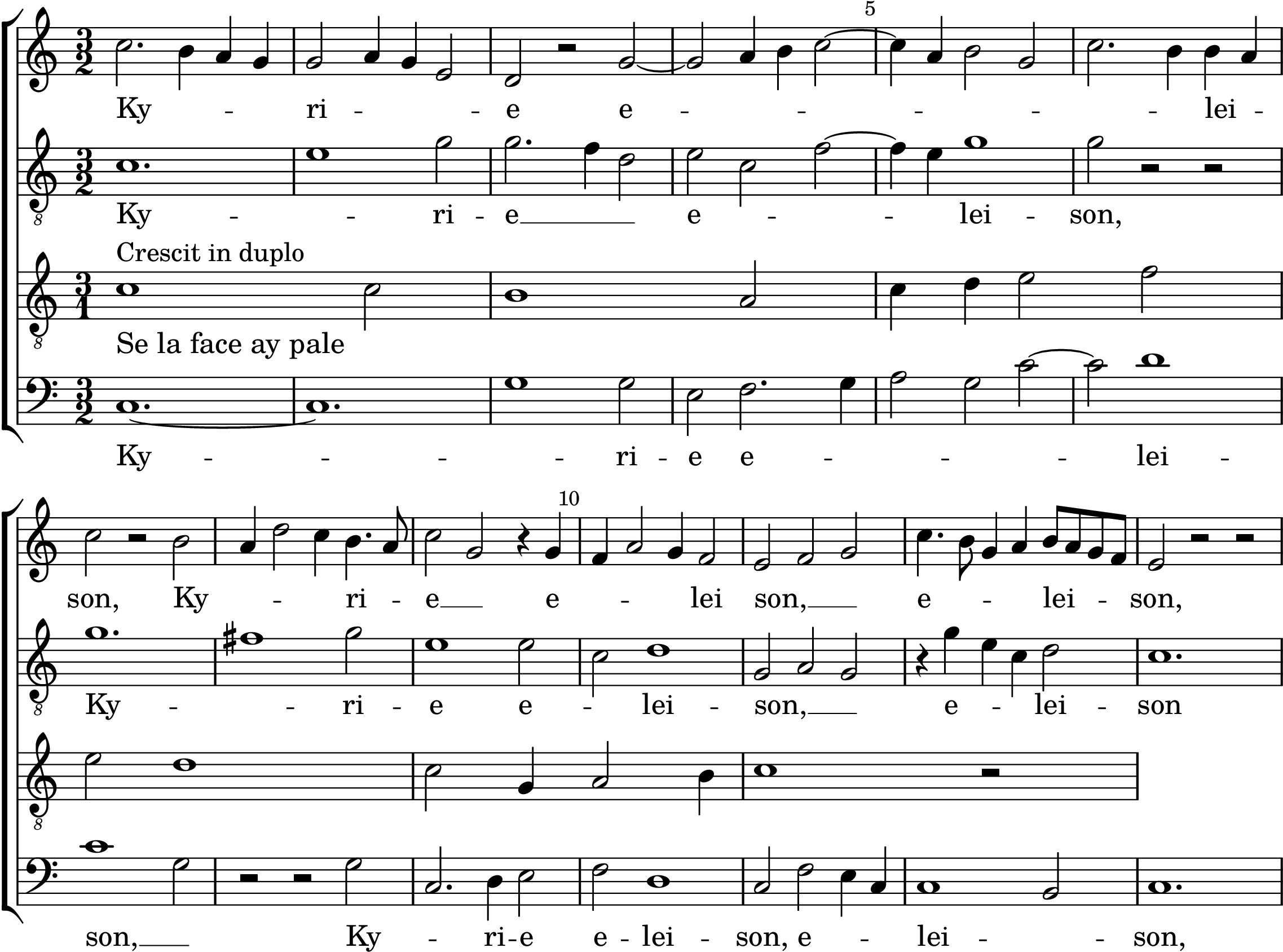

These characteristics can be demonstrated in the first 16 bars of the Kyrie below, which is reproduced from Planchart's edition8.

Figure 1. Du Fay, Missa Se la face ay pale, Kyrie I.

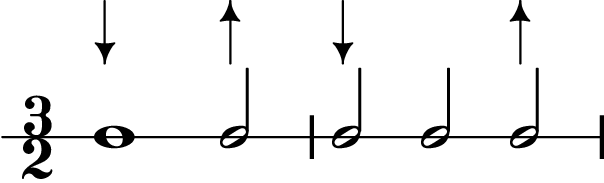

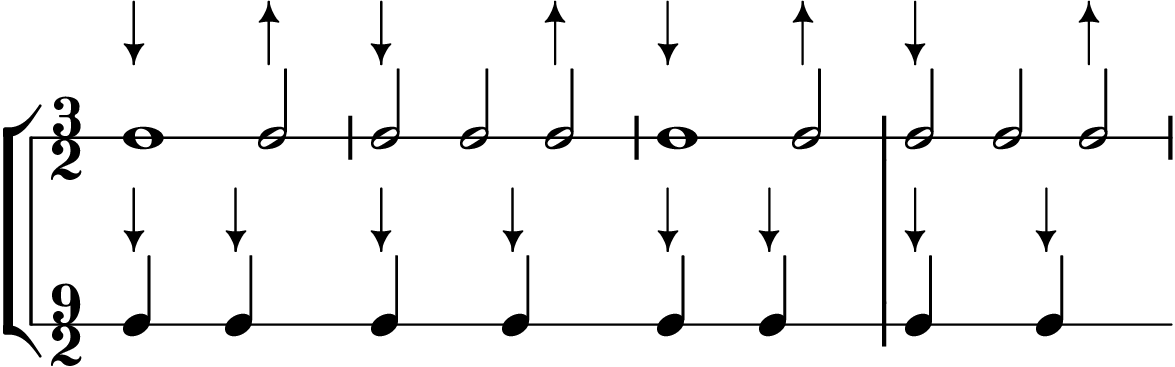

This is the only section of the piece where the tenor starts with the rest of the voices. The altus and bassus proceeds mainly in breves and semibreves, while the superius has more semininims which fills out the rhythmic spaces. The innate rhythm of the Tempus Perfectum mensuration is the alternation between a strong (imperfect) breve downbeat and a weak semibreve upbeat along the course of "One-two… Three | One-two… Three" (see the diagram below), which can be observed in the tenor and the bass, whose notes fall invariably on this rhythmic grid. The beat is reinforced by the superius, which sings against the beat by deliberate syncopations (Bars 4-6, 8, 10) and provides a good deal of forward momentum to the music.

Figure 2. The tactus in a ternary metre. Downbeats indicated by down arrows, upbeats indicated by up arrows.

More significantly, there is one other layer of rhythmic complexity above the interplay between the two lower free voices and the upper one. Here we see the purpose of the strong ternary rhythm created by the free voices, for this enhances the potency of the clash between the conflicting rhythmic model in the tenor. Although the tenor is also in a straightforward Tempus Perfectum mensuration, its in two-fold augmentation puts it at odds with the other voices by creating a strong hemiola tendency as its semibreves are equivalent to the imperfect breves of the outer voices, naturally merging two bars in the free voices in one.

Metric conflict between hemiola and double augmentation. Although the two down beats are not in alignment, they still fall at the metrical division (minim).

The conflict can be observed most strongly in bars 2, 5, 7 and 10, where the tenor asserts its own rhyhmic indepence by changing notes in the middle of a held note in the other two lower voices. This subtle but unmistakable tension is present in all the sections of the mass where the tenor in double augmentation, and sets Du Fay's mass apart from its contemporaries such as the Domarto and Ockeghem which has the tenor proceed in tandem with the pulses of the free voices.

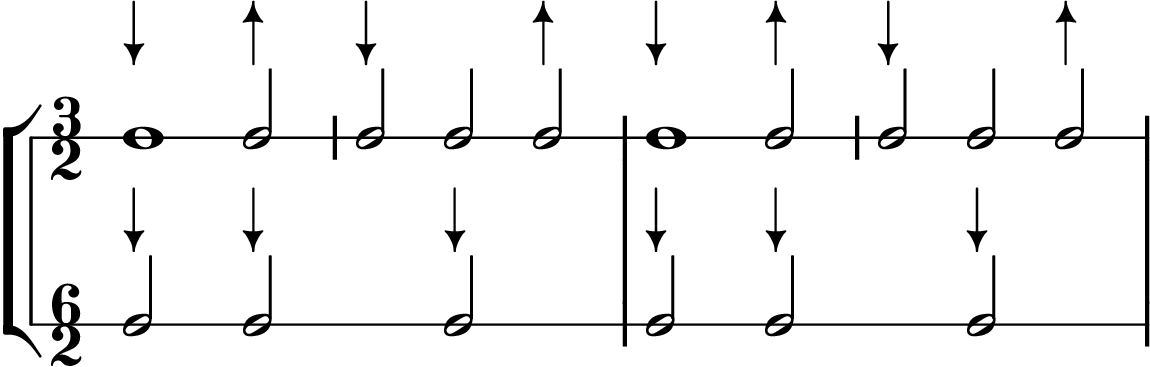

Figure 3. Du Fay, Missa Se la face ay pale, Et in terra

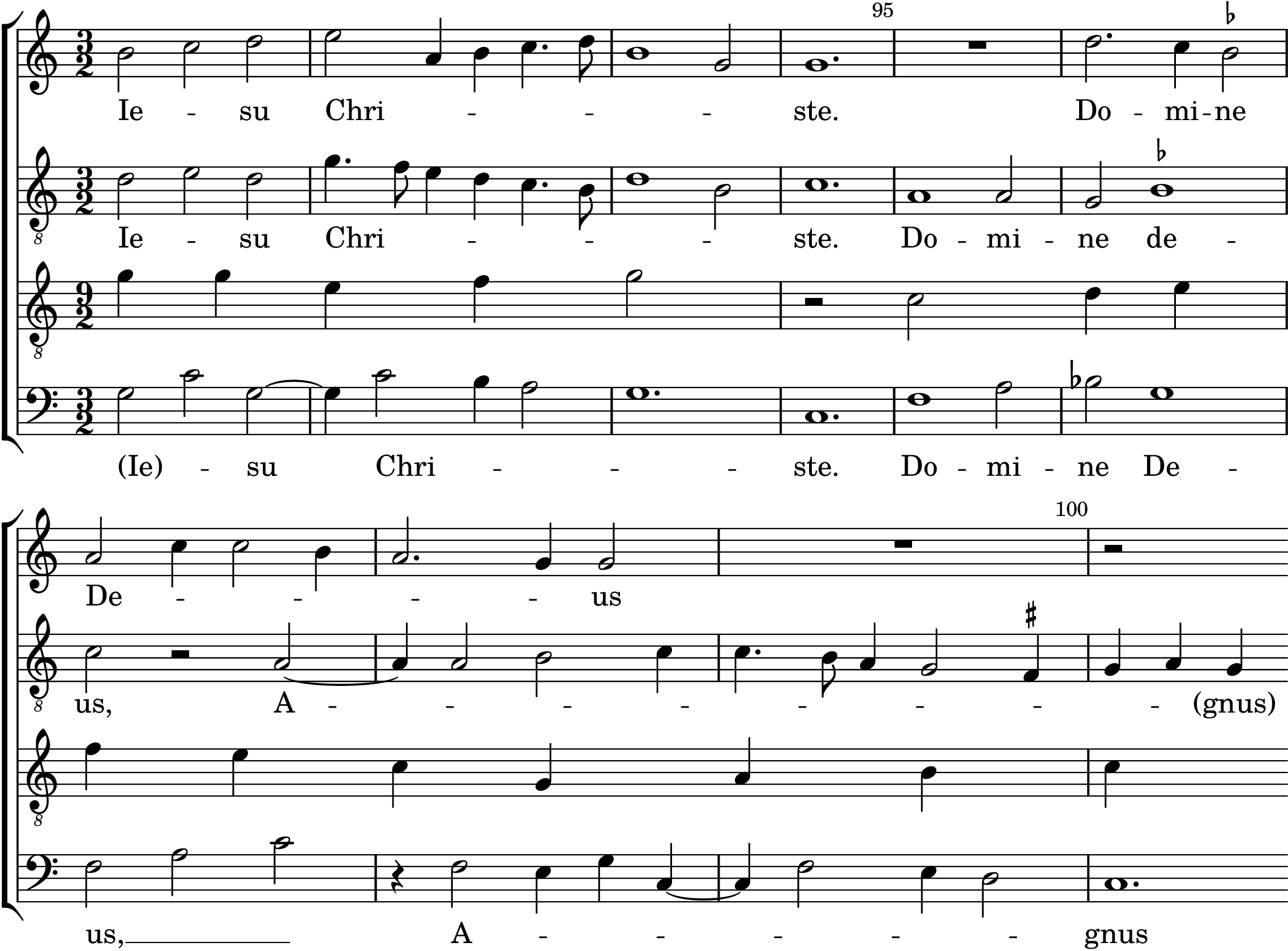

This tension is enhanced in the Gloria and Credo, where the tenor proceeds from triple augmentation down to double augmentation, and finally statement at original speed. The tension is exacerbated since under triple augmentation, the clash between the tenor and outer voices becomes that of a directly 2 against 3 conflict instead of the more subtle organisational discrepancy of hemiola.

Figure 4. The conflict between duple and ternary rhythms. Note that the lower voice fall between the beats of the upper voice.

Some of the most exhiliarating moments of the mass are places where the minim in the tenor, augmented to dotted semibreves, clash against the semibreve beat of the free voices. Structurally, this arrangement also makes a lot of sense. As the rhythmic conflict decreases between the tenor and the free voices decreases, it is compensated by the increase in speed and raw drive, which combine to form a satisfying conclusion in the final "Amen".

Sometimes, these traits stand out more strongly in their absence. Compared to the Domarto and Ockeghem masses then, Du Fay's mass appears positively exuberant. Perhaps some difference is due to the difference in characteristic of the cantus firmus. Du Fay's jaunty ballade moves in short, highly profiled phrases, and serving up cadences on a dinner plate. As Edward Wickham mentioned in the notes to Ockeghem's Caput mass, to wrangle a cadence out of the Caput tenor, especially as it lies in the bass, takes some contemplation. In both the other masses, the expression is more muted and subdued. But because the tenor moves at the same rate as the other voices, and all the voices equally engage in syncopation and other behaviour which underlies the meter, there is no rhythmic tension as set up in Du Fay's mass. Their lengthier and irregular phrases also contribute to this.

In short, Du Fay's voices are less independent, since they need to serve a functional role within the whole composition, as opposed to maximise the melodic interest in each line as Domarto and Ockeghem has done. To his contemporaries, the trade off must have been obvious, where the increased comprehensibility comes at a cost of what many others have considered to be the primary concern of the 15th century musicians, which is the linear beauty of the lines, and maximising variety. To a modern audience conditioned to the highly choreographed style in the classical tradition, this may have been less obvious. But it nonetheless should be maintained that the contemporaries would not have found the Domarto or Ockeghem less expressive. Indeed, the manuscript evidence suggests quite the opposite, since the Domarto far outnumbers the Du Fay in number of sources, and as Wegman has shown, initiated a whole school of competition9. While Du Fay's mass, as observed by Sherr, is copied in rather a haphazard fashion, and in the current state is unperformable in two of the three manuscripts which it survives (it survives in complete in the third)10. Another reminder that modern reception in no way indicative of the 15th century reception.

Modal characteristics

Perhaps the characteristic most audible to modern audiences is the strikingly modern sound world created by the largely consistent and unambiguous modal characteristic of the piece. To our ears it sounds effectively like C major, which is a bright, spacious mode with little excursions and ending on an irregular final. Du Fay has manage to reinforce this modal coherence at every turn, and this characteristic sound world is perhaps the largest difference between this mass and the staunchly Dorian alternatives of Ockeghem and Domarto.

The history of the modes is a complex one, and in particular its application to polyphonic pieces and its role as either prescriptive or descriptive by no means straightforward. Theorists have also tried to reconcile the three main strands of Church modes with the modes of classica Greece, while recently the likes of "tonal types" have been introduced in order to facilitate our understanding of it11. Meanwhile the invariable mixing of plagal and authentic modes, which are modes sharing the same finals but having ranges a 5th apart, in polyphonic composition means that in effect the mode of only some of the voices would have to be selected as the mode of the piece.

The tenor and altus appear to be in the plagal mode of C (mode 12 or Hypoionian as designated by Glarean), and the superius and bassus in the authentic (mode 11, Ionian). There are two problems with this assignment: before Glarean, no theorist have described any mode which ends on C; the tenor ends on C but all other voices end on F, which is all the more remarkable since that no voice have the one signature flat which is typical for F modes, and therefore the majority of Bs would have been sung as hard Bs or B naturals, further tilting the favour towards the C side. As we shall see however, this apparent contradiction does not interfer with the immediate aural result f the mass.

Throughout the composition, Du Fay have emphasised, in decreasing significance, cadences around three notes: C, F and G. This is carried out through cadences, mostly between the cantus and tenor, but also reinforced by the bassus with V-I motions; through effective harmonic functions in the bass by holding strategic notes for certain durations; and finally, through the characteristic profile of the melodies in each voice, we shall see how each of them contribute to establish the modal identity of the piece.

The primary determination of mode, more so than the melodic quirks and harmonic empahsis, are the cadences. In addition to forming the musical articulation by wrapping up phrases and marking out the ending, cadences have a role primarily in establishing the mode of the piece. In fact, the very definition of a cadence relies on a purely intervallic concern, without reference to its syntactical significance. The cadence is essentially, the moving of two voices in contrary motion from an imperfect consonance to a perfect consonance12. Since they invariably occur on the downbeat or initiation of rhythmic units, and they invariably involve a suspended dissonance which heightens the effect of the resolution, they are the most powerful reinforcers of mode when they are used on the most significant pitches of the mode. This can also be reinforced by other voices, particularly the bass in making V-I motions which is the strongest confirmation of the cadences' finality, hence its use at the end of every major section of the piece.

A typical cadence in C. The suspension and contrary motion between the two voices to the octave are the signposts of a cadence.

Cadences round out each phrase, breaking them down into smaller pieces, allowing them to be grasped by the mind more easily compared to long winding phrases with no termination, and also confirm the mode in the process. Since cadences help this conceptualisation even without rests, they improve comphrehensibility without crippling the forward momentum of the piece. This style is shown in its extreme in the confident idiom of Antoine Busnoy, where cadences saturate almost every other bar of his smooth flowing polyphony. Du Fay's application is less extreme, but is easily detected. In the opening 13 bars of the Kyrie, it occurs five times.

| Bar | Voices | Pitch |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | A, B | G |

| 6 | S, B | C |

| 8 | S, T | C |

| 10 | T, B | C |

| 12 | A, B | C |

The overwhelming majority of the cadences are in C, which acts to establish the mode, their regularity are also admirable. We can also observe the way the cadence regulates the ebb and flow of the music to create a high point of musical drama. The distance between first and the second cadence lasts twice as long as all others. This is also significant since the first cadence is the only one not in C, this establishes a tension which is exacerbated by the lack of an expected resolution on bar 4. In addition, both the tenor and the bass start to climb to the top part of their range, reaching their highest notes in the section right at the point of the cadential preparation. This magnificent energy requires moderation which explains the regularity of the cadence to re-establish C as the modal centre.

The question remains concerning why Du Fay would end the mass on F instead of the C mode which he carefully establishes throughout the piece. It could not be a desire like Ockeghem to exploit the particularly rich conflict between the modes, for the D and G modes are clearly antagonistic, with the defining pitchs of the mode, the third and the sixth being major in the G mode, but minor (or altered to minor) in the D mode. This is not the case when the C and F modes are contrasted, for their thirds and sixths are both major. Indeed, the F mode hardly ever appears in the interior, and the ending must be confirmed by a extension where the C-F cadential motion is repeated up to four times in the bassus. The same procedure also occurs in the Ecce Ancilla Domini mass, where the chant in the pitch of G ends in C. It is perhaps wrong to impose any modern sensibility of "return to tonic" in these music, but the primacy of the modal final is very strongly emphasised in theoretical writings. Perhaps the placement of the non structural voices is of less importance than the most important voice, which is the tenor. Or that Du Fay wanted to end his Bassus-Altus duet in the proper plagal mode. Or even the lessening of tension by ending at a 5th below the pitch of the tenor is considered a more effective ending. In any case, we are not treated with the shock of a foreign destination at the arrival of the cadence, but rather a relaxation of tension which does not seem entirely out of place.

Musical Intertexuality and the intermingling of the Sacred and Profane

Finally, one apparent vexing question must be addressed. Why borrow the music from a pre-existing composition, and more importantly, why borrow an ostensibly secular piece which may well be disconnected with the liturgy? This question can be answered somewhat satisfactorily with the unique circumstance of the Du Fay mass, but for the wider context of the existence of these chanson masses which borrow from explicitly secular polyphonic pieces, Professor Jennifer Bloxam has provided an overview together with a list of all the earliest chanson masses up to about 1470 13.

In sum, masses based on love songs, like the devotional pictures, religious tracts, and writings presented here, can be usefully understood as the courtly expression of new trends in religious thought and Marian worship that go beyond and in some crucial ways contradict the analogical model that dominated ways of thinking prior to the fifteeth century. Binding these diverse modes of expression together is a common reliance on the language of secular love, be it musical, verbal, or visual, as the communicative vehicle best suited to transport the listener, reader, of viewer into contact with the divine.

Fifteenth century audiences clearly saw the matter of incorporating secular tunes in sacred repertoire differently. For them it is not a matter of irreverence but another facet of the intermingling realms of the sacred and profane which was never really clearly distinguished. On the other hand, the specific circumstances of Du Fay's mass and its connection to the Holy Shroud is however given by Robinson 14:

Motivated by the emotional art and literature of his time and by the arrival in Savoy of the one relic that had the capacity to stir devotion above all others, Du Fay repurposed his ballade as a striking meditation on Christ’s visage and physicality within the musical structure of this Mass. In so doing, he set the course for himself and others who likewise would employ secular songs as symbols in their own works.

It is perhaps significant that as the 15th century drew to a close and these rich extra-musical associations became weaker, the chanson mass saw the end of its heyday and began to be replaced by motet masses in popularity. A crucial distinction must be therefore made on the practices of borrowing before and after this period of change. In contrast to the stylistically homogeneous soundscape of the mid 16th century, during the second half of the 15th century when the chanson masses first emerged, there is a sharply pronounced difference between masses and chansons, as confirmed by the categorisation by Tinctoris of the first into the highest category of music, and the latter to the lowest. We should not read Tinctoris's comment as denigrading the prestige of the chanson in preference of the mass, but rather that the centre of his aesthetic principle is varietas, and this can be best achieved in the breadth of the masses. To look at it another way, the relative short length of the chansons meant that varietas was not an operating principle, and it thus developed a more subtle, focused, and stylish atomsphere that is far removed from the somewhat rigid and blunt organisation of most masses.

The transformation of a song tenor into a mass tenor then, is fundamentally a destructive process, where almost everything that's unique and good about the song are obliterated, and in its place the mass strews together from its remains something almost unrecognisable. By the time of Obrecht, some efforts were made in order to replicate, in a sense, the style and spirit of the original polyphonic composition, but for Du Fay the cantus firmus remains of purely structural interest. None of the jaunty, irreverent rhythms of the original ballade is replicated in the mass, which joins over the sharply delineated phrases with smooth flowing polyphony that maintains a sense of metrical irregularity, befitting the dignity of its proportions.

In summary, the question "why did Du Fay write a mass on a song tenor" can be answered in many ways. Because the tenor provides special significance for the occasion the mass is used to commemorate. Because a tenor provides the scaffolding of the piece which fixes the compositional plan and facillitates fitting of the other voices around it. Also because the mass has always been a cannibalistic genre which takes musical inspiration from other sources. Finally, because like all composers, Du Fay must have been intrigued by the purely music challenge of reinterpreting something he's written some years ago, and relished the joy of casting it in a new light and giving it new life.

Review

With the above context about the mass in mind, we can then settle to proceed with the major modern recordings of the mass. First must raise the issue of scoring.

Footnotes

For a modern edition, see the new "Du Fay Opera Omnia Part 3: Ordinary and Plenary Mass Cycles-4", edited by Alejandro Planchart at DIAMM.

Wegman, Rob C. “Petrus de Domarto’s ‘Missa Spiritus Almus’ and the Early History of the Four-Voice Mass in the Fifteenth Century.” Early Music History 10 (1991): p272.

Robertson, Anne Walters. “The Man with the Pale Face, the Shroud, and Du Fay’s Missa Se La Face Ay Pale.” The Journal of Musicology 27, no. 4 (2010): 377–434. doi:10.1525/jm.2010.27.4.377.

Sherr, Richard. “Thoughts on Some of the Masses in Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, MS Cappella Sistina 14 and Its Concordant Sources (Or, Things Bonnie Won’t Let Me Publish).” In Uno Gentile et Subtile Ingenio, edited by Gioia Filocamo and M. Jennifer Bloxam, p322. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2009. doi:10.1484/M.EM-EB.3.2700.

Though the tessitura of all voices are higher than normal for both the altus (which frequently sounds an A4) and the bassus (which never dips below C3). Possibly the piece was sung at a lower pitch standard in order to make these ranges more comfortable for a male ensemble.

Strictly speaking the Gloria and Credo are not fully scored in the sense that they too alternate between fully scored periods and periods of free alteration between the three free voices. But such an alteration includes inside the subsection.

Planchart, "Du Fay Opera Omnia", p3. Following Planchart's practice, the note durations have been halved in the transcriptions.

Wegman, "Petrus de Domarto's 'Missa Spiritus Almus'", p270-272

Sherr, "Thoughts on some of the Masses", p323

Wiering, Frans. The Language of the Modes: Studies in the History of Polyphonic Modality. Psychology Press, 2001. p10-15

Though from the 15th century onwards, standardisation meant that the perfect consonance have been either the unison or the octave. For more information see Atwell, Scott David. Cadence, Linear Procedures, and Pitch Structure in the Works of Johannes Ockeghem. Michigan State University, 2001. p16-25.

Meconi, Honey. Early Musical Borrowing. Taylor & Francis, 2003. p6-28

Robertson "The Man with the Pale Face", p433.